The Neuropolitics of Burnout

At its core, burnout is rising costs and sinking rewards. That’s the essence. Burnout has a lot of neuroscience research behind it, but that’s what it comes down to.

When life and the world get stressful, your brain notices, and starts to get into “fight or flight” mode more readily. Being in this mode makes work more difficult, but doesn’t increase the emotional reward you get from completing it. This growing gap between expected and actual reward messes with your dopamine circuits, further stressing you out. Lather, rinse, repeat.

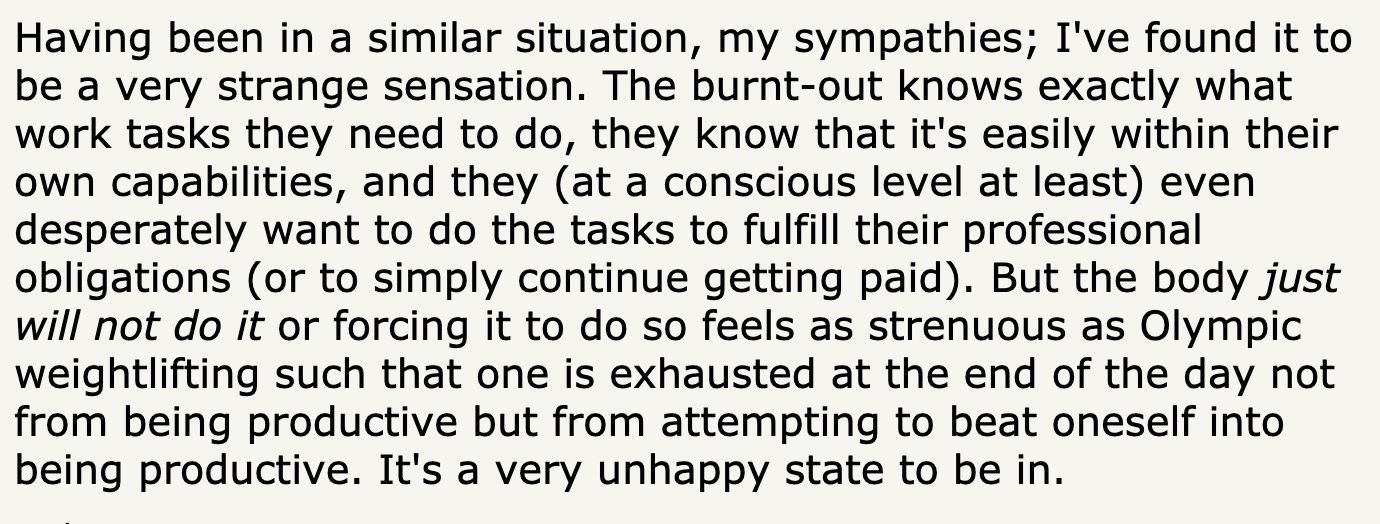

The actual state of “burnout” is the end result of this process. This comment from Hacker News describes the subjective experience of it pretty well:

Burnout is linked to things like depression, anxiety, stress, and Zoom fatigue, but it’s not exactly any of these. It can affect people who’ve never had a Zoom meeting or mental health diagnosis in their lives and it can affect people who barely notice it on top of similar feelings they’ve had for decades.

The great misframing

The biggest problem with the term “burnout” is that in a truly Orwellian way (less like 1984, more like Politics and the English Language) it frames the issue around the individual. It makes everything about that which burns out, not the fire doing the burning.

I won’t pretend there’s nothing individuals can do to mitigate it. Getting outside, exercising, and cultivating hobbies that allow frequent feelings of incremental progress are what neuroscientists tend to recommend.

Increasingly, though, it’s not up to individuals, and pretending this is so is like pretending the right way to reduce wildfires is by spraying individual trees with fire retardant.

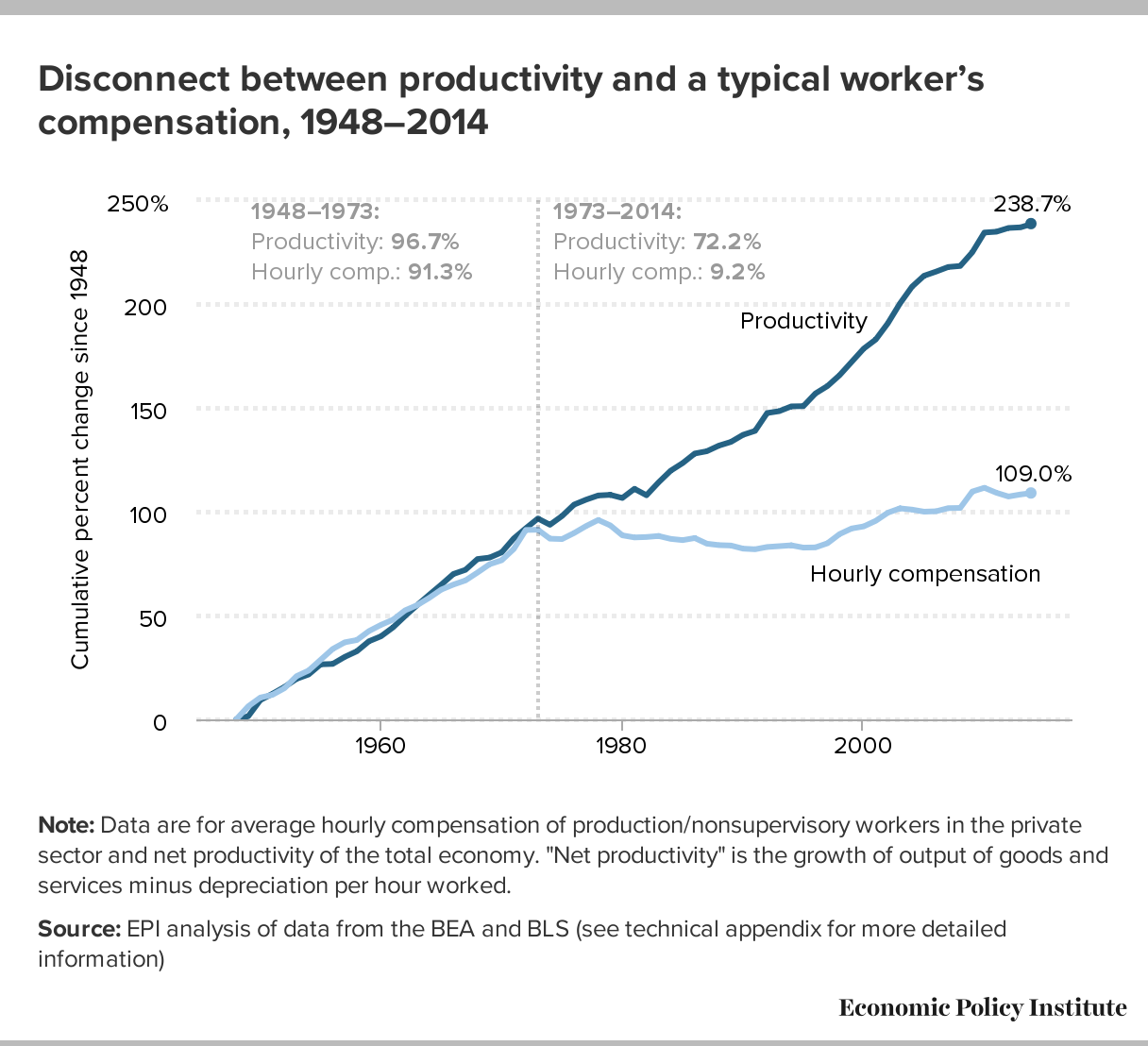

It’s now widely known, for example, that worker purchasing power has not at all kept up with worker productivity since the 1970s. Minimum wage hasn’t even kept up with inflation. This, as much as any other recent political or ecological catastrophe (though many are related), is the fire.

Everything costs more relative to what we have, not just in terms of effort but also in terms of money — housing, healthcare, education, you name it. Wages and benefits simply haven’t kept pace.

More broadly, the things that may have made us feel accomplished earlier in life — acing tests, doing well in sports, etc. — tend to have no real benefit or analog in the working world, and cannot detract (or, increasingly, distract) from the economic and political turmoil around us.

Rising costs, sinking rewards.

Neuropolitics

For the same reasons they started muddying the links between cigarettes and cancer in the 1950s, executives will continue to muddy the issue of burnout.

With one hand, they’ll just keep pushing the envelope of how much burnout is acceptable: they’ll force people into overtime work that destroys their mental health. They’ll break the law to interfere with unionization efforts. They’ll make workers pee in bottles, then lie about doing so.

With the other hand, they’ll wage a war of public opinion. They aim to convince us that, because it can feel so personal and biological, burnout must be an entirely individual problem, and in no way a collective one.

Even workers at cushy tech jobs see it. Startups have long used mantras like “build fast and break things” and “fast-paced culture” to gloss over organizational chaos, the results of which are disproportionately handled not by the executives whose jobs it is to wrangle that chaos, but by workers within the company.

Companies like these increasingly chafe against the shift to working from home not because it hurts productivity (the numbers are in: it doesn’t) but because it reminds us, contrary to their narratives about work being a “family” or “mission” (which make people more willing to put up with BS), that work is still, at the end of the day, an exchange of money for labor.

Workers in all industries have to organize to buck this trend, and increasingly, they are. The recent DoorDash strike and New Yorker unionization are promising examples. There are clear ways of winning new laws and policies that companies can’t sabotage. They’re easier said than done, but not unheard of.

For this to happen, though, people need to know that “burnout” is not some new and fleeting cause of discontent. It’s been exacerbated by pandemic-related stress, and by ways in which companies have ignored or mishandled that stress. It’s been caused, however, by decades of class warfare coming home to roost, plain and simple.