Torches on a checkerboard

Allotment, alienation, and a reckoning centuries in the making in the northwoods of Wisconsin

1. Largemouth bass

Gusts meet the wavy glass of the lake’s surface, pushing blobs of static over a dark blue screen. Flecks of yellow and red mottle the wall of green in the distance. A loon howls.

I feel a bite on the rod and pull it up. Something thrashes. I reel it in. I pinch the line just above its head and hold it up. It’s a largemouth bass about the size of my hand with eyes like black marbles. I wrangle its slimy body off the hook and toss it back. It hits the water with a decisive plop and swims off.

2. Walleye

It has become an annual ritual on the tranquil lakes of northern Wisconsin. As the sun sets behind the dense pines that surround Lake Nokomis, tribal drumbeats signal the start of the Chippewa spearfishing season.

While the Indians steer their boats into the calm, dark waters, angry protesters try to drown out the drums with air horns, whistles, and taunting choruses of songs with such lyrics as "Where have all the walleye gone?"

…

There is little evidence that the walleye population is near extinction. According to the state Department of Natural Resources, which sets the safe harvest level for fishing, sport anglers caught 670,000 walleyes last year vs. only 16,000 speared by Chippewa fishermen.

— Walleye War, TIME Magazine, April 1990

Warming lake and stream temperatures are altering habitat conditions, favoring some species and threatening others. Walleye, one of the most sought-after species among Wisconsin’s anglers and a cold-water fish, has been declining over the last 30 years. Largemouth bass, a warm-water fish, have been increasing.

— Warmer Waters Could Impact Sport Fishing in Wisconsin, U.S. Geological Survey, 2017

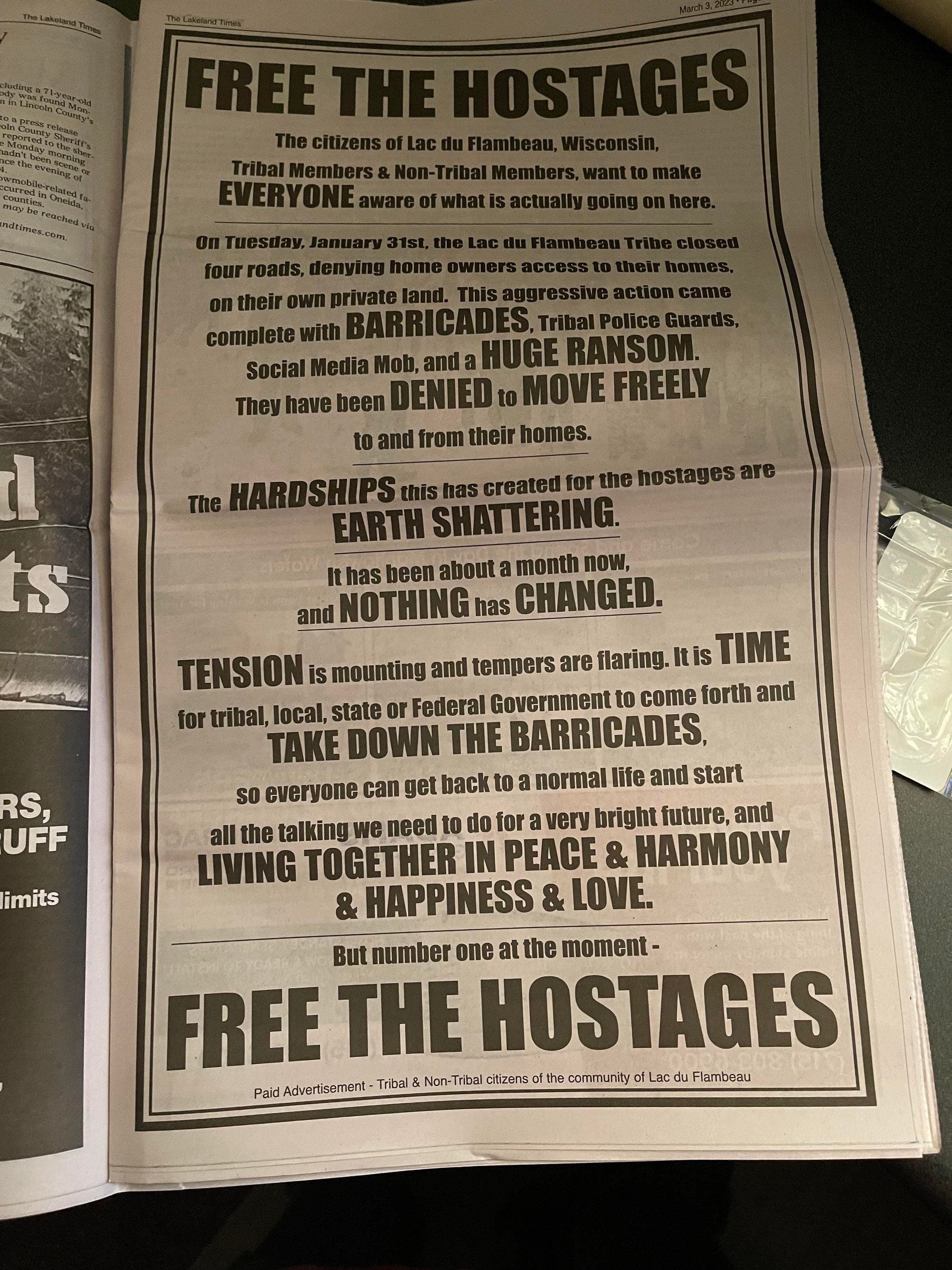

3. Barricades

[Dennis] Pearson and 60 other people are blocked from driving to their own homes. They’re caught in the middle of a complicated and stalled negotiation that is once again pitting members of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa against non-tribal members.

Barricades erected by the tribe on Jan. 31 are preventing the residents, 19 of whom live there year-round, from using portions of four roads to reach 73 non-reservation properties in the town of Lac du Flambeau, which lies largely within the historical boundaries of the 86,000-acre reservation in Vilas County.

More than 30 years after the contentious debate and violent protests over spearing walleye in off-reservation waters, this latest property rights dispute centers on the tribe trying to keep land they say has been taken from them over many decades.

— Roadblocks put homeowners in the middle of dispute between tribe, town of Lac du Flambeau, Wisconsin State Journal, March 2023

Northern Wisconsin land owners have asked a federal judge to order the removal of barricades set up by a Native American tribe in a decade-long dispute over roads it claims were illegally built on tribal land.

…

Tribal leaders said they resorted to the extreme measures after 10 years of failed negotiations with title companies representing property owners who have expired right-of-way agreements to use the roads on tribal land. The title companies want permanent right-of-way agreements, but the tribe has only been willing to offer 25-year leases, according to a statement last month.

“Essentially, they are asking us to give up our land. We have given up millions of acres of land over generations. We now live on a 12-by-12 square mile piece of land known as a Reservation,” the tribe said in a Feb. 9 statement. “This is all we have left.”

— Lawsuit: Remove blockades in Wisconsin tribal land dispute, AP News, March 2023

4. Torches

One-seventh of the Town is part of the Chequamegon National Forest…The remaining six-sevenths of the Town are part of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Chippewa Reservation.

…

The band acquired the name Lac du Flambeau from its gathering practice of harvesting fish at night by torchlight. The name Lac du Flambeau or Lake of the Torches refers to this practice and was given to the band by the French traders and trappers who visited the area.

…

About 52 percent of reservation land in the Town is held in trust or is Tribally owned for Tribal members' housing needs and economic development pursuits. The remaining 48 percent of land is “fee land,” which is privately owned by individuals, most of which are not Tribal members.

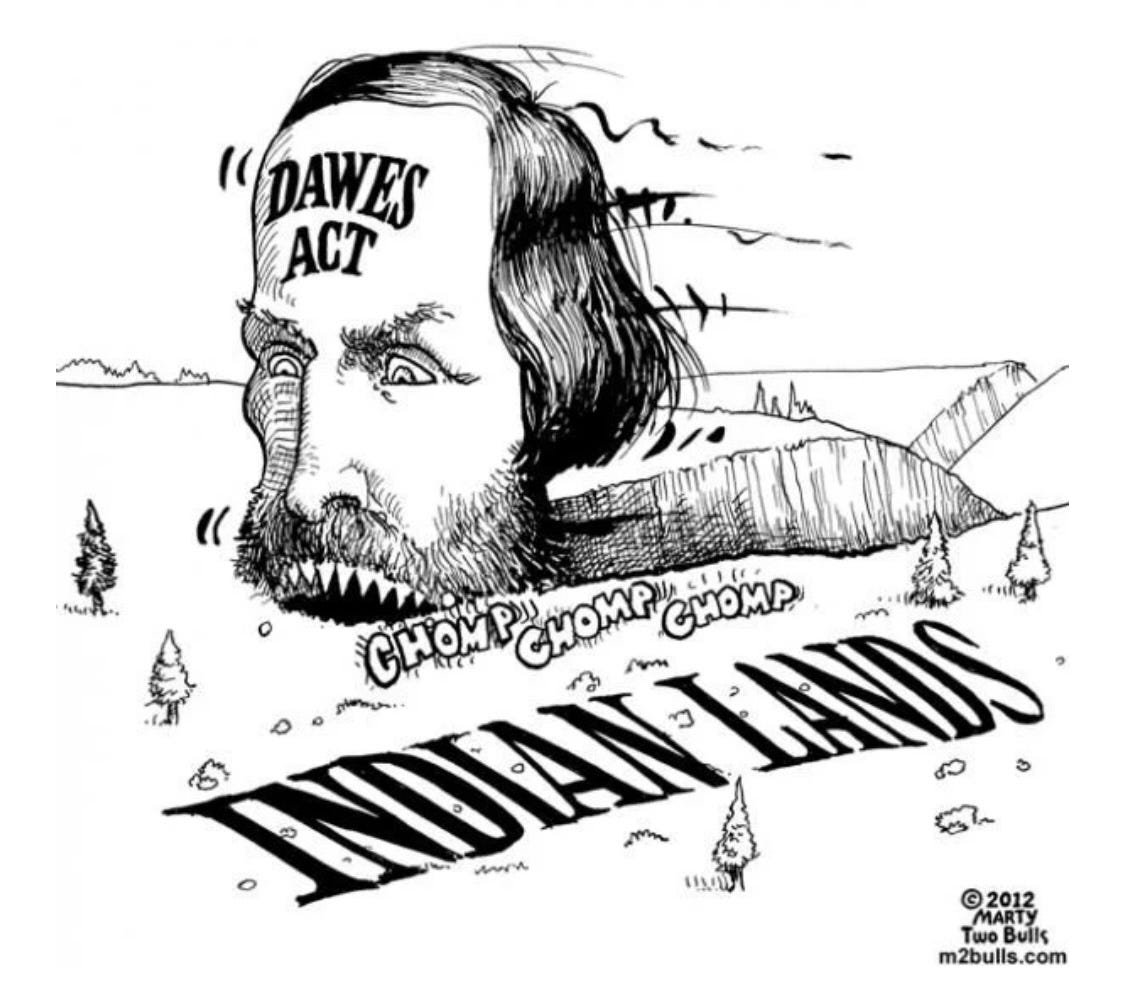

Under the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887, each Native American was provided a piece of property within the reservation as their own private property. Land that is currently in private ownership was “trust land” that was sold to willing buyers by individual Native Americans under the Dawes Act.

— Town of Lac du Flambeau Comprehensive Plan, December 2008

[The Dawes Act] is a mighty pulverizing engine for breaking up the tribal mass.

— Merrill E. Gates, Secretary of the Board of Indian Commissioners, 1900

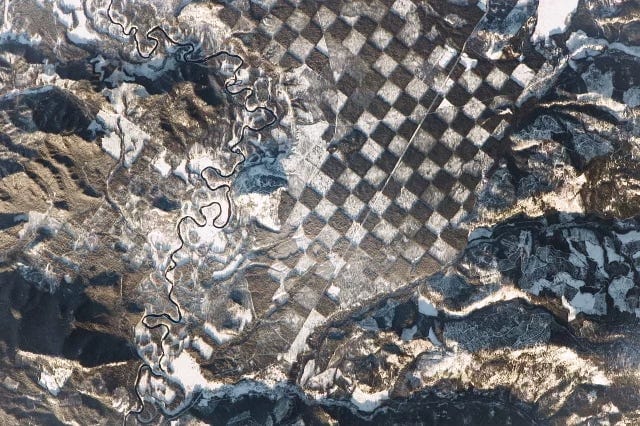

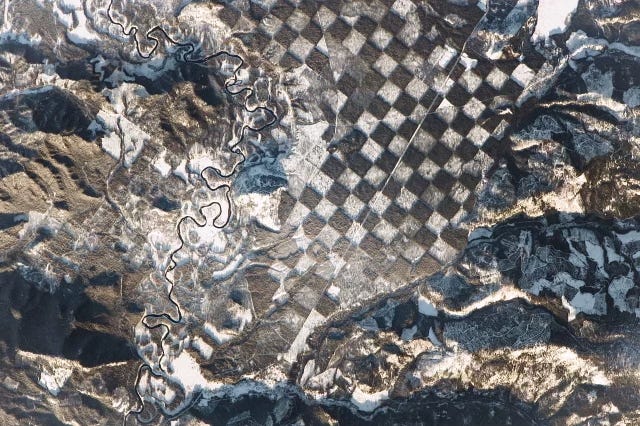

5. Checkerboard

In 1903 the Secretary of the Interior deemed the Lake Superior Chippewa to be ready for allotment. This included the Lac de Flambeau band…The Reservation was divided up into individual allotments not to exceed eighty acres of land. The land was carved up in a checkerboard fashion to hasten the demise of the Reservation. Land in between the allotments was put up for sale to land speculators.

The impact of the Dawes Act was the same in the Northwoods as in other places. It devastated tribal communal culture and left the people of Lac de Flambeau in poverty. The Ojibwe were vulnerable to those who would take advantage of their unfamiliarity with U.S. land laws, and in this way sacred sites like Strawberry Island were lost as predatory speculators moved in to take the best lands.

Few people cared and little help was offered until the election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932…The Indian New Deal ended the Dawes Act, but by then the damage had already been done. A 1936 survey revealed that 25 million additional acres of land were needed throughout the country to permit Native Americans to support themselves on the same level as a poor rural white family.

…

Wherever allotment had taken place, Indigenous peoples were left with the most marginalized land. This was true at Lac du Flambeau as well, where many tribal members were landless and living in abject poverty. In fact, the survey singled out the Lac du Flambeau Reservation as being “the most hopelessly checkerboarded Reservation” in the entire country. The ravages of allotment had left nearly all Reservation land alienated from the tribe. Most of the desirable shore fronts had been taken over by whites and used for resort hotels or cozy summer homes, all of which was surrounded by poverty.

— History of Allotment at Lac du Flambeau, Gary Entz for WXPR, August 2020

The Dawes Act inherently called for the fractionization of Indian lands as the ownership of the land is passed down to the heads-of-household children and so on, dividing it up with each further generation.

…

After his mom died, Peter [Lengkeek] and his six siblings received an acre of land in Montana. Peter and his brother drove to Montana to see the land. He went to the title office to find out his land's exact location—what he discovered was unbelievable.

“On that one acre of land,” he laughs. “There are 938 of us who are owners.”

— Native American land and loss, Native Hope blog, February 2021

6. Cash for dirt

Nineteenth century Eastern reformers falsely told a story that Indians recognized no private property in land. In fact, an analogy for almost every significant element of Anglo-American property law is present somewhere in…Indian property systems. Rights to use a specific parcel of land, to exclude others from it, and to allow others access to it were common. Interests similar to easements, licenses, profits-à-prendre, life estates, leases, timeshares, condominiums, corporate titles, co-tenancies, and defeasible fees can all be found. Mechanisms appear for inheritance and transfer of rights to other Indians. A more accurate, more true, story would have been that Indian property systems differed from Anglo-American law in how they recognized and ordered a wide range of property rights in land. Nonetheless…reformers were correct that Indians viewed land differently from white settlers. For many Indian tribes, their land was at the core of their identity as peoples.

One piece of land was not equivalent to any other. Land was not fungible. Rather, their specific land was a gift, given to them to live upon, but also given to past and future generations. Accordingly, many Indians felt a strong religious obligation to protect their territory, to safeguard the land that future generations would need to live upon, and to honor the past generations who had in prehistory migrated long distances before arriving where the People were to live. The land could not be sold; one could sell neither the future, nor the past.

These and similar views of the land, long articulated at treaty negotiations and often reported to white settlers, fed into the reformers' image of Indians as naive, wild, and free, ignorant of the civilizing institution of private property. When outsiders heard Indians argue that land could not be sold, they concluded that the Indians had no private property in land. The outsiders heard wrong. When Indians denied that land could be sold, they were doing so in reference to sales and cessions outside the tribe, transfers which threatened their very identities as peoples…Their [Quaker] “Friends” promoting allotment used that resistance to charge them with a deficiency in private property rights…Indians tried to tell them differently; but they, and Congress, did not listen.

…

Far from replacing common ownership with private property, the Dawes Act allowed the federal government to replace these multiple, functioning property systems with a single, dysfunctional system, one that failed to provide for property transfers and rational inheritance. Indian property law was effectively ossified, dependent on the occasional meddling of Congress and regulation-writing officials in Washington for change. It remains so today.

— Retelling Allotment: Indian Property Rights and the Myth of Common Ownership, Kenneth H. Bobroff, 2001

A federal judge on Tuesday dismissed a lawsuit seeking to block a northern Wisconsin tribe from barricading roads on its reservation, saying the non-tribal land owners who brought the action didn’t have a case under federal law.

…

US District Judge William Conley in Madison signaled in June that he would not force the tribe to remove barricades while the lawsuit played out. In an order issued Tuesday, he dismissed the lawsuit altogether and sided with the tribal council, saying it has sovereign rights over the roadways and that a federal court does not have the jurisdiction to force it to keep the roads open to the public.

…

The US Department of Justice filed a separate lawsuit in May, asking Conley to force the town of Lac du Flambeau to pay damages to the tribe for failing to renew the land agreements.

In negotiations with the town, the tribal council adopted a resolution that month calling for access payments to be set at $22,000 for the month of June and increase by $2,000 every month going forward. So far, the town has complied.

— Judge Dismisses Lawsuit Seeking to Remove Lac du Flambeau Roadblocks, Harm Venhuizen, AP, August 2023

7. Different

MARISA WOJCIK: What do you think is most important, especially for a non-Indigenous audience to understand about this situation especially if they feel like already most of the finger pointing goes to the tribe?

RICHARD MONETTE: Well, I think they have to understand that all this — the difficult, terribly difficult history that people say, “well, I wasn't there, I didn't have anything to do with it” — okay, but you're there now. And it very clearly derives from that, and we have to honestly assess that, and take some ownership of that. And I think that's one of the more difficult things.

And then understanding sovereignty which people don't. Why do these Indians wanna be different? Well, how would we like it if Iowa came and took over Wisconsin, right? Well, why do we wanna be different, right? That’s their answer. Whatever we can come up with, they can come up with the same ones and maybe even then some, right?

…

Imagine the feeling of irony if you're a tribal member with this whole history of imposed American propertization, right? And then you're looking at a bunch of non-natives telling you that they didn't quite understand the property stuff at play here, right? It's hard for them to buy.

— Richard Monette on Native sovereignty, owning land, and law, interview with Marisa Wojcik, March 2023

This land belongs to us, for the Great Spirit gave it to us when he put us here. We were free to come and go and to live in our own way. But white men, who belong to another land, have come upon us and are forcing us to live according to their ideas. That is an injustice; we have never dreamed of making white men live as we live.

White men like to dig in the ground for their food. My people prefer to hunt the buffalo as their fathers did. White men like to stay in one place. My people want to move their tepees here and there to the different hunting grounds. The life of white men is slavery. They are prisoners in towns or farms. The life my people want is a life of freedom. I have seen nothing that a white man has, houses or railways or clothing or food, that is as good as the right to move in the open country, and live in our own fashion.

— Chief Sitting Bull, 1882

8. Treehouse

When I was eight, my siblings and I helped my stepdad build a treehouse. The tree was behind our backyard on a patch of land between our property and the Contra Costa Canal Trail. Shortly after we finished it, the city told us we had to tear it down.

We were citizens. We could have organized to change the rules. But we were busy. We had work and school. Who has the time to get involved in all that? Or what if that’s the wrong question? What if the question is whether we have time to not get involved?

What if the way indigenous Americans see land is not an inconvenience that they’ve put in our way but the opposite? What if it’s something that, were we to internalize it, holding it up against the bureaucratic tyrannies and climate catastrophes we seem unable to stop inflicting on ourselves, would save us?