Cognitive clutter

So much fine print, so few who want to read it

The term “cognitive clutter” seems like one that pop psychology should have claimed years ago. A quick search shows it only being mentioned by a smattering of sources — parenting blogs, LinkedIn posts, Hacker News comments.

The areas make sense, though. Education, product design, software engineering. Our world runs on knowledge and data. We rely daily, hourly even, on complex infrastructure, physical and digital. We send young people off to spend their weekdays learning.

It’s grown unprecedented not just in scale, but in style too. That is, in our past, despite there being no end to the watering holes and hunting grounds and social relationships one could spend one’s mental energy keeping track of, there were physical limits. These things were real, space- and time-bounded, situated in our environment, brimming with connections and context.

Now we have digital storage; now, more often than not, the context around the facts we see and learn has collapsed. Any two things you see in a row on Twitter or TikTok or your TV are likely to be unrelated to each other, your community, or even you, despite being algorithmically tailored to your interests.

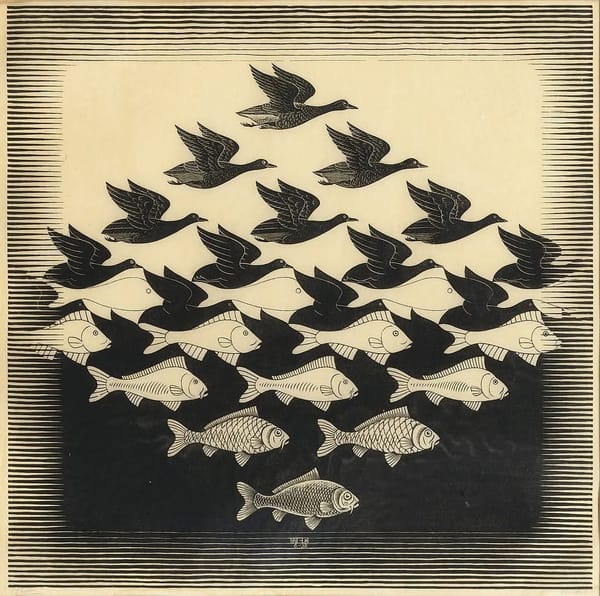

This is how cognitive clutter differs from “cognitive load,” a related but different and well-established term. Clutter is not necessarily about “how much” of something your brain is doing in a short span of time, but about how far afield, in how many directions, it has to extend itself — how many separate balls of messy, chaotic information it needs to wrangle and untangle.

Humans can keep up with surprisingly high learning demands — we have ways of compressing information into less complex forms, like chunking it and mnemonic devices — but institutional momentum and computer storage can be like jet fuel for this problem, pushing the complexity of a product or work environment beyond what any individual person can conceivably deal with.

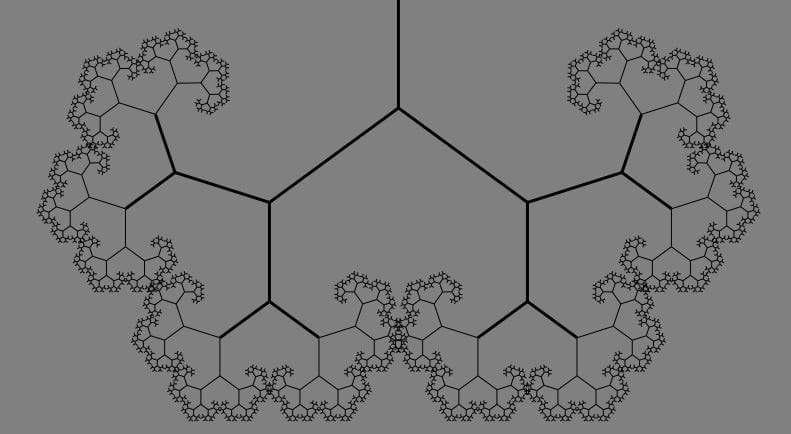

As companies, for example, build and change course and build and change course, flailing to increase their bottom lines, that complexity worms its way into convoluted pockets, like the pathways of the kidneys or lungs, curling into increasingly tight and hard-to-reach little balls. In an eternal and unforgiving game of hot potato, various poor saps periodically have to venture out into those little pockets of complexity and sort them out.

A college senior works on wrapping her head around 7 different subjects for 12 weeks, then another 7 for the next 12 weeks. A software engineering manager wraps her head around 7 different areas of her company’s codebase to get a project done on time; once that project is done, 7 new areas.

Clearly it’s not just about students and engineers. Parents feel this trying to figure out what’s healthiest for their kids. Consumers feel this. Even as tech companies like Apple and Amazon get more consolidated, which you’d think would simplify things, complexity leaks out to the consumer, in the form of labyrinthine tech support threads and developer docs.

People in countless lines of work feel this. Companies cut corners in industries not limited to ones that CNN anchors would consider “knowledge work,” “white collar,” and the like. Any company with changing product offerings and machines can involve high cognitive clutter. (On top of that, customer-facing jobs at such companies, unlike engineering jobs, frequently have emotional humans to deal with at the same time. Café workers at airports, incidentally, are all going straight to heaven.)

Being in such a mode for too many hours out of the day, failing to rest and to let your mind exercise “diffuse mode” thinking as opposed to “focused mode,” is a drain on this second mode. People in high-performance situations — sports psychologists, Air Force pilot trainers — are beginning to notice this as it has direct bearing on their work, i.e. making people perform mental tasks better, and especially under some kind of pressure.

The chronic demand of a cognitively cluttered environment, of being beset on all sides by it, is not exactly a balm for one’s psyche, even if it can be fun to engage in when playing some card game or fixing some interesting work problem.

The amount of information we consume in an hour online is comparable with the amount our ancestors in the 1800s consumed in weeks or months. The long-term effects of this on the brain are only just beginning to be elucidated, with books like The Shallows by Nicolas Carr giving a glimpse.

We don’t know everything, but we know costs exist here, just as they do with cigarettes and fossil fuels. And no one, especially not the companies contributing most to them, is footing those costs, reading the fine print on that invoice, leaving it to bewildered individuals.

Such clutter, such mazes of red tape and esoteric jargon everywhere you go, is sort of the result of carelessness, but not really. It’s not quite like someone throwing a candy wrapper out a car window. It’s more subtle, systemic, large-scale.

I’m a broken record about these sorts of problems, but ignoring their nature, merely going with their flow and capitalizing on them — the only thing an individual can really do —helps no one.

Cognitive clutter comes from corners getting cut, so that projects get out on time, so that investors get a quick return. A company’s overall lack of process, not any one person, causes a buildup over time of cluttered (or absent) information about a product you’re making, a service you’re offering.

The real-world effects of this complexity fall on individual people in ways widespread and diffuse as well as specific, bursting out in pockets of fiasco and spectacle. I can snatch them out of the air around me, they’re so easy to find.

Take the collapse of FTX, a crypto exchange whose founder back in April quite literally explained to his audience the Ponzi scheme nature of his industry. Were most of the people who got swept up and munched by the crypto craze ever going to have read and digested that interview? No. How many of those , if forced to read it, would have been convinced of their mistake? Not all.

There was too much complexity for most people who got involved, too many technical details, too much fine print; they painted over it with a narrative. “With crypto, I’m sticking it to the big banks, to the establishment, and I’m gonna get rich doing it.” The ideal American scam, taking advantage of people with hype and technical supremacy. Dr. Oz and Elizabeth Holmes could never.

It’s one thing that this is happening to willfully-ignorant suckers. It’s one thing for me to run into issues around cognitive clutter in my own professional life that I can’t really, fully, totally address unless they’re addressed on a wider level.

But it’s another entirely, and an infuriating one, that the same is true for so many other people, well-meaning people, in more dire and far-reaching ways every day. In healthcare decisions and legal proceedings and educating children, cognitive clutter lets corporations take advantage of people. It makes people mentally exhausted; it makes them not want to question and address the frittering away of dwindling resources by the rich, but be passively entertained by it instead.

Only individually do we get scammed and deceived and overwhelmed by this complexity. Individually, humans are frail in the face of cognitive clutter, and the corporate deception that flourishes there, amid isolation and uncertainty.

As the saying goes: apes together strong. Unlike a rabble of corporations in a trench coat posing as a country, we have the ability to dust off time-tested ways of protecting our attention from clutter and getting truth from crowd efforts. You can read about those time-tested ways on the Internet, but of course, we’ll never actually manage to use them if we stay too long there, where so much of the clutter actually is.