Pick your Kool-Aid flavor or someone else will

The Merry Pranksters, Blood Meridian, and the inevitability of sacrament

I.

Doing jazz band as a kid was a double edged sword. The experience was frequently corny. The music it exposed me to was worth it.

The vocabulary it gave me is made of moods and vibes more than phrases. There’s no way to translate it like a language. You have to experience it.

II.

For, as it has been written:…he develops a strong urge to extend the message to all people…he develops a ritus, often involving music, dance, liturgy, sacrifice, to achieve an objectified and stereotyped expression of the original spontaneous religious experience.

Christ! how many movements before them had run into this selfsame problem. Every vision, every insight of the original circle always came out of the new experience…the kairos…and how to tell it! How to get it across to the multitudes who have never had this experience themselves? You couldn’t put it into words. You had to create conditions in which they would feel an approximation of that feeling, the sublime kairos.

— Tom Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, 1968

III.

Kairos is an ancient Greek word meaning 'the right, critical, or opportune moment'. In modern Greek, kairos also means 'weather' or 'time'.

It is one of two words that the ancient Greeks had for 'time'; the other being chronos. Whereas the latter refers to chronological or sequential time, kairos signifies a proper or opportune time for action. In this sense, while chronos is quantitative, kairos has a qualitative, permanent nature.

— Wikipedia

IV.

It is within your power to experience a crowded, loud, slow, consumer-hell-type situation as not only meaningful but sacred, on fire with the same force that lit the stars — compassion, love, the sub-surface unity of all things.

Not that that mystical stuff's necessarily true: the only thing that's capital-T True is that you get to decide how you're going to try to see it…You get to consciously decide what has meaning and what doesn't. You get to decide what to worship.

Because here’s something else that’s weird but true: in the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship.

And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship — be it JC or Allah, be it YHWH or the Wiccan Mother Goddess, or the Four Noble Truths, or some inviolable set of ethical principles — is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive.

— David Foster Wallace, This Is Water, 2005

V.

Some people like to describe Anton Chigurh as like the ‘Angel of Death,’ but I think the point of the end of No Country For Old Men is that he’s not, he’s just another man.

Judge Holden is like full-on, he just like is violence incarnate. What’s kind of weird is that he’s depicted as kind of Buddha-like. He’s got a very round body and face and he’s often seen just sitting very calmly and smiling gently.

There’s an amazing scene about how Judge Holden found his crew, when they were on the run and out of gunpowder, and he leads them to saltpeter and sulfur, and the last chemical he needs can be found in urine. I think it’s the ammonia. So he tells all the men just to “piss, piss for your lives!”

And he sits there in a pit, like waist deep in urine and saltpeter and sulfur, just laughing, bare-chested, slapping this mixture on his chest. He is being baptized for them in piss and brimstone, and the result of the baptism is gunpowder, and they massacre their attackers.

Though the book has these moments of coherent symbolism, I don’t know that there’s a larger message to the story. The violence simply is, and kind of resists meaning.

— @oh_whatalovelyday, TikTok, 2022

VI.

Saturday, October 29, 2011. I stood in a crowd of 80,000 at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. I was there with the Stanford band. Our football team was in triple overtime against USC.

We had a tradition for down-to-the-wire moments. The drum major gave the signal for it. The rest of the band started an arrangement of “Mars, Bringer of War” by Gustav Holst.

The section leader of the mellophones, at that time me, plays a role in this tradition. As the trombones blared and the drums rumbled, I made my way to the front of the band, nostrils flaring. I started to gnash my teeth and scream.

The music drew toward a triple-forte climax. In the final measures, I grabbed my shirt by the collar and ripped it open down the middle.

Filing out of the stadium, our team victorious, we had more than a few beer cups thrown at us, and we couldn’t have been happier.

At the end of that football season I went to the Tostitos Fiesta Bowl in Arizona. During the national anthem an American flag covering the entire field was unfurled. A trained eagle circled down onto it. At the end of the game, about two hundred police officers, all in full riot gear, surrounded the sidelines, facing out toward the crowd.

VII.

I could sum up all of what you’ve just read in a few sentences. I wanted to give you primary sources.

We endure lengths of chronos, laundry and grocery shopping, in hopes of reaching instances of kairos that make them worth it. (We rarely realize just how internally-generated and independent of circumstance these experiences can be, as Wallace points out.)

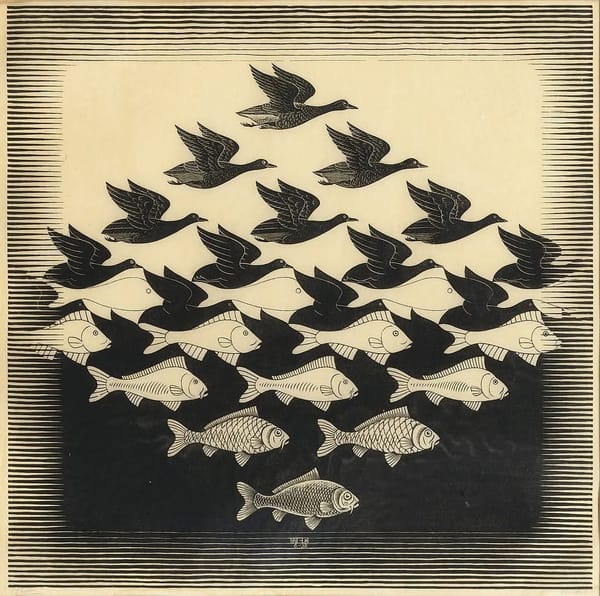

But once we have — once we’ve experienced things that let us forget ourselves and the petty drama of our lives, transcending our egos by suppressing or embracing them — we try to replicate those things, sometimes like cargo cults, trusting whatever people or sacraments are around.

Our cultures and environments push us toward certain types of Kool-Aid. Kesey, Judge Holden, and I have all gravitated toward options for transcendent experiences available to us. We all come from a particular Western tradition; as varied as our sacraments are, the connections aren’t trivial. The Stanford band and the Pranksters both got their start in the South Bay in the 60s. Both heavily involve riding on buses, wearing crazy clothes, and playing loud music at people. And Cormac McCarthy (author of Blood Meridian) was one degree removed from Ken Kesey; both were good friends with Larry McMurtry, who wrote Lonesome Dove.

Kesey wanted a new kind of movement, where people generate kairos independently and unfiltered, yet the way his movement organized itself was the opposite. It was largely filtered through him, and largely enabled by external (and therefore bannable) substances like LSD (not to mention a truly shocking amount of amphetamines).

Do we now, in 2022, have better options?

Not really. Sure, community living and experiencing the Now and all those things that make Kesey’s (and even Judge Holden’s) group desirable for any human to join in the first place are known about. They’re written about and peddled by all manner of people in America. The country is a hotbed of people selling each other forms of white patriarchal violence and atomization as the only ways to achieve kairos.

But few grassroots group experiences are available to us. We have bread and circuses — the occasional music festival, Burning Man, Netflix. In the middle of the song America by Simon and Garfunkel, about what sounds like an otherwise exciting and life-affirming cross-country trip, there’s a line that goes “I’m empty and aching / And I don’t know why.”

People like Reagan and Thatcher have helped to forcibly atomize people. Blowing up existing trends, they’ve further discouraged their countries from cooperating for any collective purpose or collective good other than buying shit, asserting that the only greater structures worth having are the nuclear family, Christian churches, and the Market.

This has consequences.

I’ve written about this, the criminalization of cooperation, as well as a countervailing force: our desire to return to a “magical empowerment of feeling.” This combination is like a tube of toothpaste being squeezed.

We’re rarely deliberate and careful with creating our Kool-Aid, instead letting our sacraments get chosen and delivered by a callous market. We flock to parasocial gatherings on the Internet where our desire for crowd-driven flow and fiero is redirected toward personal consumption. Online interaction isn’t about unity and understanding, but steaming piles of half-true gotchas.

Our desire for transcendent experience therefore oozes out in haphazard and sometimes deadly ways. Addiction, cults of personality, and the like; outbursts of senseless violence and bigotry coming from disturbed young people who see no value, no potential for kairos in their future, or worse — who think violence is the best way to get it; cool kids in Dimes Square acting like they’re resisting fake wokeness and instead openly reinforcing fascism in their art.

In a way, given this climate, it’s a lucky accident of history that the crowd at USC was merely unimpressed by us, even amused, only tossing beer cups and not bludgeoning us to death like a drunk British football crowd in the 1980s. They may have even liked that we were speaking their language for once, one of over-the-top fanfare, rather than purely making fun of them as usual.

The liberating and terrifying truth, pointed out by Wallace, is that it’s not really an accident. Despite those nudges, despite the default settings of our culture, we get a hand in choosing. We can choose our leaders, sacraments, and objects of worship, our flavors of Kool-Aid. We choose every day.

It’s not wrong that we drink Kool-Aid. It’s not wrong that we associate, sometimes even by dissociating. What’s wrong is when we stop paying attention to what the Kool-Aid is, who provides it, and what actions it involves.

What kairos are you chasing? Are you pursuing it because it’s your default setting? Is it what you want, and how you want to be spending your time? These questions determine the course of our lives. If we don’t answer them for ourselves, others will.