End A Pandemic With This One Weird Trick!

Prologue: Utopia Denied

In college, I took a class on crowds. We learned about British football hooligans and Woodstock. I wrote my final essay on Iran’s Green Movement, a wave of protests in the summer of 2009 spurred by credible allegations of election fraud committed by the incumbent, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The challenger’s campaign used the color green.

The government suppressed the uprising. Even so, the protesters set an innovative example of how social media, mainly Twitter and Facebook, could be used to communicate and organize in real time. They also used it to draw worldwide attention to video footage of the extrajudicial killing of Neda Agha-Soltan. For reasons like these “a phone in every hand” struck my idealistic teenage brain as an obvious overall good.

To some degree, as the video evidence of George Floyd’s murder shows, this was true. Why, then, did millions take Officer Chauvin’s side anyway? It was not entirely lost on me after taking this class and later ones on social psychology and world history that crowds were easily misguided and destructive. I had the good sense to spend a few paragraphs on social media’s potential future as a haven for misinformation and shallow, meme-driven discourse.

It just made a certain sense to be hopeful in 2009. Obama’s win after eight years of Bush and “truthiness” felt like a national endorsement of sanity even if it wasn’t. Bots and promoted tweets were blessedly absent from Twitter; Facebook was not yet a bubbling cauldron of conspiracy theories. For years afterward I maintained a wide-eyed optimism about how crowds, using the Internet, could crystallize the feelings of “hope and change” floating in the air. Ah, to be young.

So what exactly happened? What denied us our utopia? What filled the Internet with ads and emptied it of trust? The short answer is “fun.” Wild, sensational, half-true stories are more fun than stories with little bias whose loyalties lie with the facts.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with fun and we can still produce the second kind of story. It’s not a matter of ability. Sites like Wikipedia and publicly-funded news sources like NPR, even if distrusted by many, are beacons of hope, diamonds in the rough. But while it can be done, and can even produce fun results, it involves hard, boring, unglamorous work by many.

The Internet is not so much about that. The Internet is about fun. People reading and watching things on the Internet don’t want a slog. You don’t want a tedious and laborious journey through a labyrinth of logic. You want a rabbit hole, awe and discovery, real stories, immersive experiences, trips through space and time on the goddamned Magic School Bus. And damn it, you deserve that. You’ve been through a lot lately.

It does, however, say something about the Internet, and about you, that you’ve now come to expect no less than this. And that’s where we begin.

I. Some Of Those That Write Op-Eds Are The Same That Push Horse Meds

I once went to watch some footage of Hurricane Ida on CNN. Before I could do so I had to sit through a flashy ad for a documentary about 9/11. It boasted of new and never-before-seen footage from the event.

A media scholar named Marshall McLuhan once said, “The medium is the message.” In other words, “examine the type of media and you’ll learn things about it; those things tell you something about all the content within it.”

What this encounter on CNN, not at all unique or uncommon, tells you about the modern Internet is a form of Rule 34 which states that “if it exists on the Internet then there’s porn of it.” In this case it’s “disaster porn,” or the exploitation of horrifying events for profit or amusement.

The Internet — silently, implicitly, as a medium and not as a sentient force — turns everything into a disaster that it possibly can, including simple conversations. Disasters evoke strong feelings, which produce clicks, which make money. That which creates outrage is amplified at the expense of that which informs. Before we dive into what that means, let’s watch it happen.

The “Discourse-To-Nonsense Pipeline,” In Three Tweets

Tweet #1

A day before their boxing match on August 29th, 2021, Youtuber Jake Paul and MMA fighter Tyron Woodley met, as is tradition, to talk trash.

Woodley, born and raised in Ferguson, Missouri, took aim at Paul’s habit of adopting bits and pieces of African-American culture like making rap videos and wearing big chains. (Paul was born and raised in a white and suburban part of Ohio, and now lives in a similar part of southern California.) “How many people in your neighborhood dress like you?” Woodley asked. “How many rap videos have you watched?”

Woodley rendered Paul flustered and speechless here. There is no true comeback. For his own benefit Paul uses the trappings of the culture Woodley belongs to. Paul’s trade, his livelihood, is showbiz, acting, putting on costumes for roles he can’t and doesn’t embody. Paul now does this sort of thing so constantly and naturally that when actually confronted and questioned about it he stutters.

Seeing Paul flail was satisfying, but I knew it wouldn’t leave a mark. It wouldn’t stick. I knew this because I am what they call “terminally online.” I’m no stranger to seeing people like Paul, and Paul himself, use the tactic demonstrated by the way he ended the interview.

He torpedoed the debate. He turned it into a farce, to whatever extent it already wasn’t one. When no one takes a debate seriously, no one (else) wins. In board games, this is what we call “flipping the table.” A player, assured of their own defeat before the game is over, flips the board, often in anger and sometimes just to be a spiteful troll. It denies other players the thrill of a clean victory.

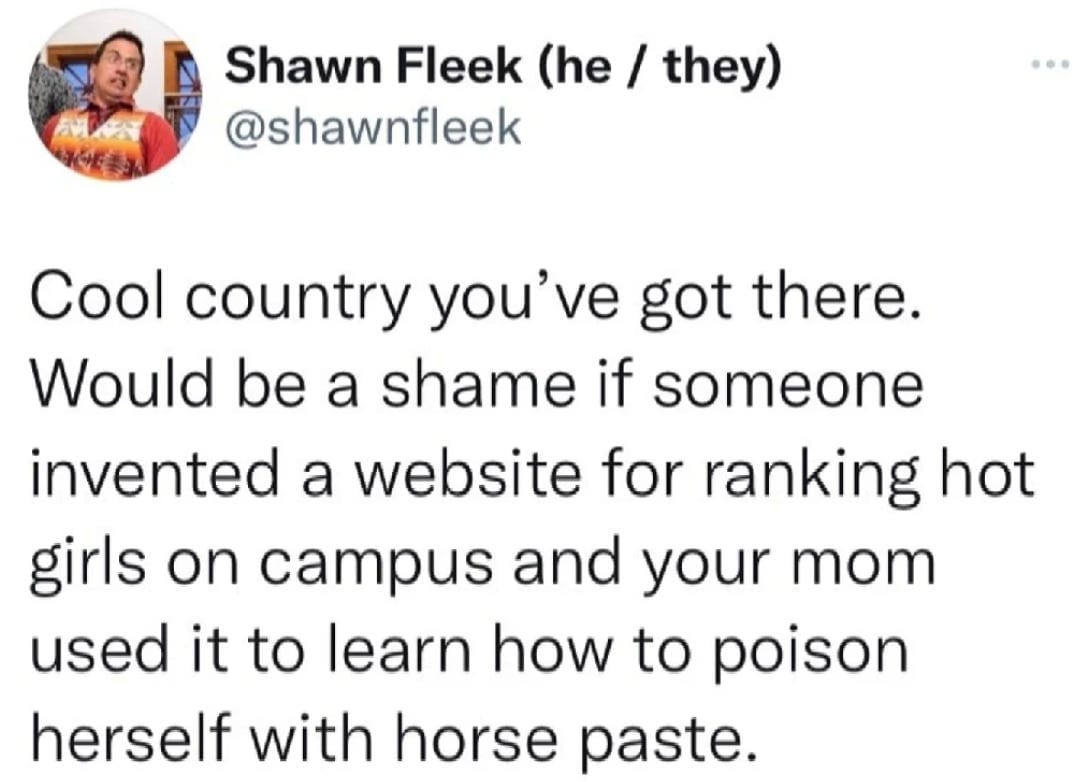

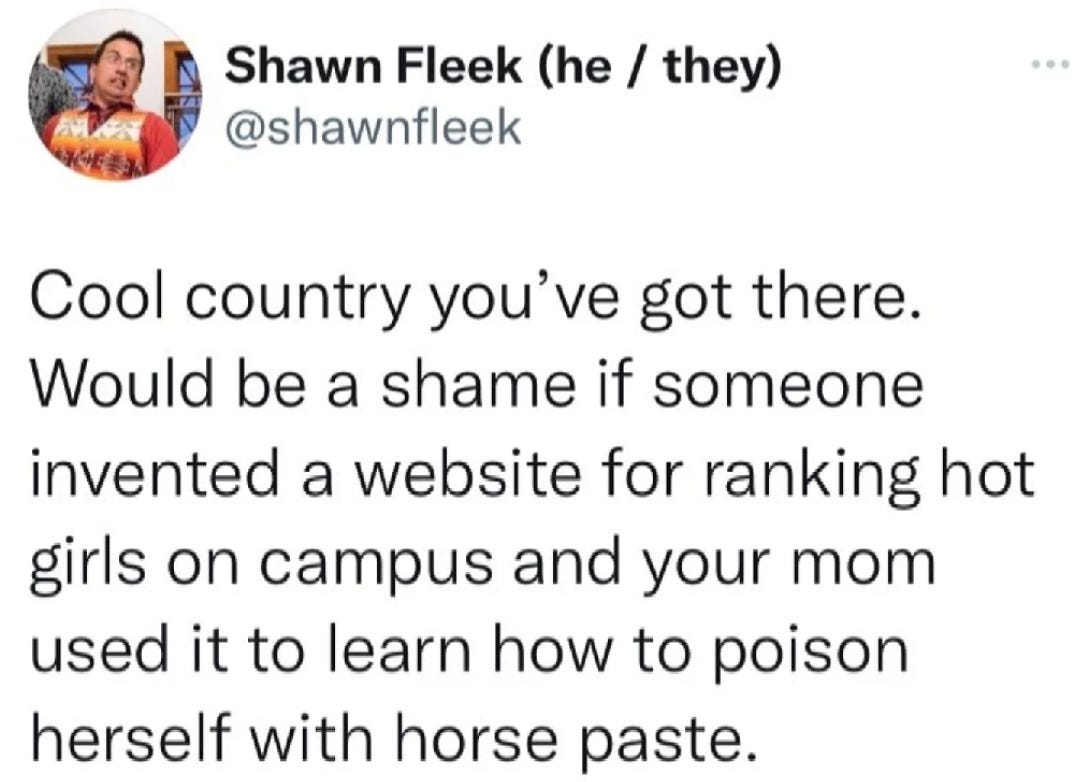

This video, while showing an IRL encounter, demonstrates how more and more discussions work, online and otherwise. They are polluted, derailed, and made nonsensical by people unable to cope with discomfort or compromise like toddlers. Hypocrisy means nothing to them. It’s often impossible to tell if they actually hate they/them pronouns and police abolition, or just enjoy sloppily debating people.

These things — their lack of conviction and integrity, their cherry-picking of “rational” arguments mixed with appeals to emotion — make them perfect tools for bigoted and powerful interests with real axes to grind.

Tweet #2

A thread is started by a woman looking for practical advice.

It receives plenty of helpful replies. It also gets mobbed by unwelcome and unhelpful partisan crusaders, furious that this woman would “give in to the patriarchy” so blindly.

The latter type of response made up many of the the top replies and sub-threads — the ones Twitter showed first — because they have the most engagement, but to read them is to enter a Twilight Zone. To read them is to be encouraged to forget practical considerations and common sense; never mind the mundane logistical scenarios potentially at play, like the wind being an issue where you live or a girl wanting to go out in a dress or skirt but return home on a bike.

Many replies pretended there was nothing else worth discussing here, no honest motive this person might have for trying to get some advice, other than the tragedy of society telling women to desexualize themselves in a world where many men just need to stop violating boundaries. That’s a real problem, and the author of the tweet probably wouldn’t, and never did, dispute that. And even if her daughter does want to do this partly (or wholly) because guys can be creeps, telling a woman she’s wrong for this because “she shouldn’t have to compensate for men’s failings” is like saying she should never carry pepper spray on principle even when it might save her life.

Sometimes, what seem like good intentions can also lead to massive table flips. The Internet doesn’t care. The Internet loves it.

Tweet #3

Earlier in the summer of 2021, a popular Youtuber by the nickname of Shoe (shorthand for her handle on most platforms, shoe0nhead) got involved in one of the messiest Twitter arguments I’ve ever seen, which is saying something because, again, “terminally online” and all that.

The claim being argued was this: if you eat meat then you have no moral justification for thinking bestiality is wrong. Both activities do, after all, involve non-consensual acts on animals, who famously can’t consent to anything.

Despite loving a good steak, Shoe disagreed with this claim. To her and many others, it’s fine to say that meat is delicious, animal sex is gross, and that’s that.

As if to put the issue to bed, Shoe tweeted the following. (The globe, sock, and rose emojis represent leftist communities with whom Shoe has a bit of a love/hate relationship, for reasons you’ll soon see.)

Another Youtuber, Big Joel, made a good video explaining this fiasco and you should watch it sometime but since it’s 21 minutes long I’ll summarize it here: with her immense audience and one out-of-context tweet Shoe slyly reframed the whole debate around a different question (“is bestiality wrong?”) than the one being argued (“is condemning bestiality morally compatible with eating meat?”).

The answer to the first question is yes; the answer to the second is no. It’s good to think bestiality is gross. It’s not good to think the emotions of a crowd at a given moment should be immune to logical criticism. This should be obvious; crowds in American history have thought interracial marriage and homosexuality were disgusting, but that doesn’t mean we should listen to them or have laws that mirror those emotions.

By engaging with the debate and then changing the question, Shoe kind of flipped the table. But she didn’t totally flip it, and this is important. She sort of wrenched it around 90 degrees. She used a form of anti-intellectualism to try and win a debate, which doesn’t completely fit with the fact that she’s pro-science and pro-socialized-medicine, but it’s part of her brand, her shtick, to do this. She calls herself a “bimbo populist,” promoting not anti-intellectualism per se but a specific kind of intellectual laziness that actually has a lot going for it.

In terms of the “is bestiality wrong” question itself, she has a point. Many on the Internet, when they see their opponent being right about something but for even the slightest whiff of a wrong reason, still fly into a frenzy.

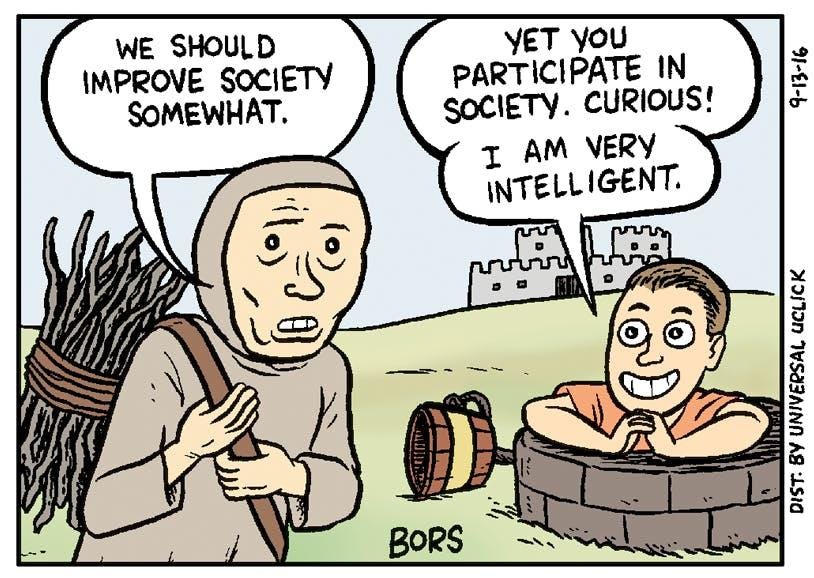

How many people, day-to-day, stop to consider all of the logical ramifications of each and every one of their actions? None, that’s who. Even if you’re both vegan and anti-bestiality, thinking you can float above this feud, you cannot escape this lack-of-consent issue. Maybe you own pets. Almost certainly you own some piece of clothing or technology built by exploiting animal or human labor. Does that mean you can’t argue against fucking animals? Does benefitting from some bad things in society mean you have no grounds at all on which to argue for its improvement?

No. We need all the help we can get. Whether or not she meant to, and whether or not she glossed over crucial points as she did it, Shoe made this debate serve a higher purpose. She — and we — do need to be able to say “fucking animals is bad” collectively even if not everyone is saying it for the “rightest” reason.

This is because there are other debates where there may be lives at stake if we can’t do so, and the debate just keeps going in circles. Shoe is guiding our focus onto a bigger problem, showing us a much bigger table flip going on. Perhaps there are some who want tables to be flipped on the Internet, everywhere and always, and in perverse ways actually benefit from this. Perhaps they want us to perpetually flounder and hand-wave so that no collective conclusion is made and no decisive action is taken because collective decisions, even if helpful to them in some scenarios, could be slightly disadvantageous to them in others.

Perhaps they even realize that people are waking up to this, the epidemic of table-flipping, but hope to convince us of the lie that without their wise and generous assistance, we will all be arguing in circles forever.

Big Disinfo

I like to read about online disinformation, which is why I’ve been surprised by how few good takes I’ve found about it. One such article recently made the reason for this click for me:

The ruptures that emerged across much of the democratic world five years ago called into question the basic assumptions of so many of the participants in this debate—the social-media executives, the scholars, the journalists, the think tankers, the pollsters. A common account of social media’s persuasive effects provides a convenient explanation for how so many people thought so wrongly at more or less the same time. More than that, it creates a world of persuasion that is legible and useful to capital—to advertisers, political consultants, media companies, and of course, to the tech platforms themselves.

— Joe Bernstein, Bad News

That “common account” is roughly this: “Oh no! Big Tech swindled all of us! But it’s okay, we — CEOs, scholars, pundits — know how their mass manipulation works now, and you should trust us to fix it.”

If you’re an executive at a Big Tech company, this lets you kick the can down the road. This lets you say: “We need to rein in our manipulation a little, just enough to make it look like we changed our ways, not enough that people stop thinking our ads work.”

Meanwhile, if you’re someone at a big news network or university, this lets you say: “Now that I’ve told you where online extremism comes from and it’s all the fault of Big Tech’s manipulation and definitely nothing else, go back to treating me as a gatekeeper of truth, please.”

The reason I wasn’t finding good takes on this, then, is that I read too much from outlets like The Atlantic and The New Yorker, where many in this second group are found, and where many in the first group (though they do this everywhere) advertise.

It’s useful for this alliance — the new-money sandal-clad Big Tech folks and the old-money suits of yesteryear who work in law, marketing, media, politics, and academia — to push this shared and grossly oversimplified story of where disinformation comes from. It’s a textbook example of Gramsci’s “cultural hegemony.” The dangerous (and false) crux of the position is that “all large crowds are swindled equally easily by ads and fake news.”

Sure, large crowds can be swindled. Yes, Trump and Big Tech played big parts in spreading doubt and false claims about the pandemic. But notice that Trump has also supported the vaccine in front of his fans and gotten booed. There are cracks forming in the uneasy alliance between Big Disinfo — corporate elites — and the millions of reactionary conservatives that they herd like cattle into online corrals. The former whips the latter into a clickbait-fueled frenzy, making money from them like a hydroelectric dam making power, benefitting from the way they troll leftists and apolitical folk who just want a functioning society. The elites want to preserve the status quo; anyone who gets their kicks from hating on those who want to improve the status quo, even a little, is their friend.

While this alliance has made some very wealthy, it has come back to bite all of us, even them, in the form of a never-ending pandemic and climate catastrophe, like when a king hires mercenaries who eventually overtake the kingdom. The corporate elite is in a bind. To keep doing business and making money, they need order. It would behoove them to offer solutions — alternatives to the Internet’s insane status quo, sorely-needed spaces where people gather and agree upon real truth.

This isn’t profitable. They don’t want better ways for big structured groups in America to make big structured decisions, lest those decisions leave them and their profits out in the cold. They don’t want you to know that the Left and Right in America have fundamentally different relationships to truth and science. They want you to believe that no good decisions can ever be grassroots or crowdsourced, and that we are all forever at the mercy of charismatic demagogues.

An entire industry has formed around this idea. Many pundits have amassed audiences (or tried to capitalize on existing ones) by clutching their pearls about the mortal threat of cancel culture and “being silenced.” They claim that any online crowd is cause for disgust and terror; that there’s as much to fear totalitarianism-wise from “woke” leftists as right-wing trolls; that the threats to free and open discourse, to truth itself, are well-balanced across the political spectrum.

This idea is a totalitarian trick. Saying all sides are at fault for a problem is a way of deflecting blame away from those who contribute exponentially more to it. Who benefits from the notion that all who voice strong political opinions online, leftists and right-wingers alike, are just crazy extremists whose brains have been scrambled by social media and can’t be listened to? Obviously it’s those who don’t want anything to be done about our big political problems. Obviously it’s the corporate and political elite who continue to block collective progress.

They get away with this because, again, they’ve convinced a large swath of the unscientific and authoritarian right wing that people calling for obvious changes, like an end to police brutality or a coherent COVID response, are akin to crowds of pilgrims burning witches at the stake or Nazis shipping minorities away to be gassed. And even though left-leaning Twitter mobs may remind us of the need for fairer ways of administering justice in large groups, even though they may hint at the importance of using reason and facts in the way we do so, they are not the ones creating that necessity. Their snarky memes and ability to turn a racist tweet into a lost job or a damaged reputation are sideshows compared to the mobs of reactionary conservative trolls whose “online mob justice” actually spills out into the real world, prolonging the pandemic and storming Capitol buildings.

It is not in our best interest to keep all crowds afraid of each other, unable to make sound decisions with each other, lost in one giant undifferentiated mass. Not all crowds are equally frightening and loathsome and easily swayed. Different mobs argue and reach conclusions differently. Some ways of doing so result in more or less accuracy, well-being, and prosperity than others. In some groups, a dictator or oligarchy makes decisions in whatever way they want. In other groups, people carefully consider information, others (scientists, experts, etc.) help analyze it if necessary, and all vote for a course of action.

History shows us how we can harness this fact on a large scale, or fail to do so. Depending on the situation we can decide which mobs to listen to more than others and benefit accordingly, or how we can decide not to, and suffer the consequences.

Beating A Dewormed Horse

Finding the Small pox to be spreading much and fearing that no precaution can prevent it from running through the whole of our Army, I have determined that the troops shall be inoculated…Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure, for should the disorder infect the Army in the natural way and rage with its usual virulence we should have more to dread from it than from the Sword of the Enemy.

In 1777, the smallpox vaccine was very much under development. “Inoculating” meant exposing someone to the disease in ways I do not recommend looking up if you’re squeamish or about to eat.

Washington naturally felt skeptical when faced with this choice. What if inoculation didn’t work? What if the British caught wind of what he was trying, realized the army was in a weakened state, and attacked early?

Luckily for America, his inoculation mandate — his bet on science — paid off. You’ve probably heard of this event by now, as it’s a popular example of the anti-vax right’s inconsistency. (They obviously don’t care much about consistency anymore, but it’s still a bad look to root for the Founding Fathers right up until they win the Revolutionary War with something “the libs” would support.)

You probably haven’t heard of Dr. Elisha Perkins. He was one of Washington’s battlefield surgeons and likely worked on some of these same troops just a couple years before they were inoculated. After the war, Dr. Perkins “developed a cure” for yellow fever. It was a pair of magnetic rods that would treat the disease by “drawing noxious electrical fluids” out of the body, or so he claimed.

In 1799, when yellow fever broke out in New York City, he got there as fast as he could. He tried out his newfangled remedy on anyone who would let him. It didn’t work. He promptly caught yellow fever and died.

In America, Washington is the one we’ve remembered, revered, idolized, and put on the dollar bill. Perkins is the one whose footsteps we find ourselves walking in.

Americans aren’t the only people in history who have struggled with fake news, propaganda, science denial, and fantastical thinking — pharaohs and people reporting on Jack the Ripper have used it — but those things have a particularly robust legacy here going back to the beginning. Jamestown colonists spent decades luring settlers by promising gold with no evidence other than “they found it in Mexico.” (Lucky for them, the natives also showed them how to plant tobacco. When they finally did find some gold there, it was in 1849, shortly after the California Gold Rush began.)

American settlers spent the next 400 years building a haven for those aiming to prove the statement “there’s a sucker born every minute.” Dr. Perkins was one of many who took the baton, whether cynically or out of sincere belief, and ran like crazy.

Countless Americans have peddled (and countless more have purchased from them) snake oils and bad businesses and crackpot theories. Alex Jones, Joe Rogan, Dr. Oz, Adam Neumann of WeWork, Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos, Billy McFarland of Fyre Festival — these are just a few of the latest and greatest runners in the relay.

We’ve turned them into billionaires and presidents. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, despite preaching Enlightenment values, waged fake news proxy wars. Ronald and Nancy Reagan sold us on “trickle down,” consulting astrologers to help them make real decisions that affected millions. George Bush sold us on WMDs in Iraq and on climate change being a big fuss about nothing, though in fairness, so did South Park.

Naturally, inevitably, there came a day, way back in 2016, when America elected a president who, far from originating this trend, simply took the lid off the box it was hiding in. He sold America no particular snake oil (we did get Sharper Image steaks) but rather the idea that snake oil was just fine. He embraced America’s preexisting notion that you can choose, on a whim or a fantasy, which facts are true, which cure is effective, and which scientist or journalist is lying, without carefully considering the evidence, or even having the training to do so effectively.

We’ve cultivated a culture so rife with con men selling snake oil, so admiring of them, that many can no longer distinguish it — or even care about distinguishing it, sometimes leading to their own deaths — from good medicine. And so, here we are, with COVID-19 ravaging the one nation with the easiest access to vaccines. In an echo of the Spanish flu pandemic from 100 years ago, many Americans are protesting masks and flocking to ineffective “miracle” drugs. They’re cherry-picking studies about drugs like Ivermectin that they want to be true. That’s if they’re bothering to look at studies at all; many are simply listening to neighbors and watching videos on Facebook.

They ignore what the vast majority of doctors and scientists say about the quality of Ivermectin’s evidence. Since March 2020, many of the same people have also ignored the hard-earned expertise of countless people who’ve spent decades understanding the biological issues, the public health issues, the physics-of-people-breathing-near-each-other issues, that are at play.

To do otherwise — admit that a bunch of liberal scientists are right about vaccines being safe and far more effective than any other preventative treatment — would be to abandon their post. It would be to admit that, contrary to what Trump told them, they can’t choose their own facts.

Instead, they put on the costume of science for their own gain (or rather, what they think is their own gain) without playing the actual part. And this “or what they think is their own gain” part is what makes this all so ripe for getting dunked on. They’re not only hurting others, as is usually the case — the virus is mutating more as they waste time, emergency rooms are filling up and preventing others from getting treatment, and think of those poor, worm-infested horses — they’re also hurting themselves.

Watching anyone be sad about Ivermectin not preventing or alleviating their coronavirus infection is like watching someone in a UFO cult be sad about getting duped for the 500th time by a leader who, every day, says “today is the day the mothership will take us away” and every day is wrong. You know there are powerful social forces at work, but there is also something pitiful, something contemptible, in their habit of going back to the cult and believing as fervently as ever.

It’s like, sorry this is happening to you, it seems like it sucks for you, but when will you wake up? When will you look for a better way?

I’m not exempt from these problems. No one is. I’ve shared fake things on accident. I, too, as you saw in the prologue, failed to learn from history; I put too much faith in the inherent goodness of crowds on the Internet.

There is a better way, though. And many people have worked very hard at it for centuries. I’ve used this quotation before, but it bears repeating, especially here:

Science is constantly proved all the time. You see, if we take something like any fiction, any holy book...and destroyed it, in a thousand years’ time, that wouldn’t come back just as it was. Whereas if we took every science book, and every fact, and destroyed them all, in a thousand years they’d all be back, because all the same tests would produce the same result.

— Ricky Gervais

So how do we use it, and get entire crowds to do so? How do we cultivate an environment where people from all walks of life can evaluate and believe true scientific claims, or trust others to do so? How do we get crowds to trust each other, and make good, informed decisions together, even — or especially — on the Internet? How do we guard against the misguided passions they can have, and the failings of individuals within them?

We have to pause our dunking, funny and warranted though it may be, and collectively do something about the mobs we’re dunking on — the ones holding us back from ending the pandemic, be they corporate elites or conservative suburbanites. At a certain point, the table of “people dunking on each other’s misfortune” needs to be flipped, or at least temporarily left alone, even if the side of science has the moral high ground. A new game, one that gets people to wise up — or at least one that lets us protect ourselves from them, since many don’t want to wise up — needs to be played.

Why, fundamentally, do crowds do what they do, especially on the Internet? What do they want? And how do we harness what we find?

II. Flow and Fiero

A crowd wants unity. It “wants” this in the way plants “want” to move toward the sun, or positive electrical charges “want” negative ones. A crowd clumsily oozes and lurches in some direction that’s more emotional than physical. Like a person, it’s constrained by human laws, but propelled by natural ones.

What are those emotional directions? It can depend on things like why the crowd gathered, who’s in it, and what it wants, but there are a couple directions that are close to universal.

One of them is ‘flow,’ heavily studied and popularized by a psychologist named Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi. Individually, it’s when you’re fully immersed in a task that you enjoy for its own sake, and is in a sweet spot between “too easy” and “too hard.” During flow, time melts away.

If a crowd succeeds at something (often by applying flow toward a common goal), they’ll also achieve a feeling called fiero, the “hell yeah my team won” feeling:

Fiero is the Italian word for “pride,” and it’s been adopted by game designers to describe an emotional high we don’t have a good word for in English. Fiero is what we feel after we triumph over adversity. You know it when you feel it — and when you see it. That’s because we almost all express fiero in exactly the same way: we throw our arms over our head and yell…Scientists have recently documented that fiero is one of the most powerful neurochemical highs we can experience.

— Dr. Jane McGonigal, Reality is Broken

These emotions, experienced with others, build unity like little else can. Gustave Le Bon, one of the first people to study crowds rigorously, broke down how this happens into three distinct stages: submergence, contagion, and suggestion. You lose yourself in a crowd; you grow susceptible to influence from others within it; finally, the entire crowd becomes highly susceptible to influence from elsewhere — a leader, an event, a perceived enemy.

The drive for unity has powerful effects on individuals. “Groupthink” has more names, effects, and manifestations than you can shake a stick at, from conformity to herd mentality to “the bandwagon effect.” Experiments both obscure and famous (like the Milgram, Asch, and Smoky Room experiments) show how readily we ignore our own beliefs — our own sensory input, even — in favor of group harmony.

Groupthink can unify a crowd toward a common goal; too much of it can make a crowd immune to logic. It can reinforce positions that feel true because it feels wrong to disagree with the crowd, whether or not that position is based in fact.

Does this mean crowds are destined to do evil and stupid things? Of course not. There’s rich evidence of crowds making better decisions than individuals, and of doing great things individuals can’t. In particular, we know some things that make them “smarter,” namely a diversity of opinions and (rational) deliberation.

Deliberation can go wrong, and that’s where the Internet throws a wrench into things. Even outside the Internet, it makes bad things happen if not done right. It can strengthen groupthink. Because the wrongest opinions are the most confident, it can encourage polarization, especially in crowds with diverse opinions. It can cause a group to do something no one in the group even wanted to do, or spread an idea with no basis in fact.

The Internet, in its current state, does not bring out the best in crowd deliberation, demonstrated well by those taking Ivermectin for COVID. Demagogues with no scientific background reach millions on social media by telling them what they want to hear. “Scientists are engaged in a liberal conspiracy against us. The hundreds of thousands of COVID deaths aren’t actually from COVID. The history of vaccines stomping out horrible diseases should be ignored because this vaccine was ‘rushed.’ The new variants’ effect on the vaccines renders them useless, but also the variants are fake somehow.” The list goes on; it’s groupthink at its worst. False claims multiply, thanks to a strong resistance to doubt when it’s warranted and amplification of doubt when it’s not.

Filter bubbles encourage a deadly combination of this groupthink and a blinding desire for fiero — “sticking it to the other guys”. Anti-vaxxers see an undifferentiated mob of angry left-wingers yelling at them, not caring to categorize those urging sanity into “Big Pharma reps who want money” versus “scientists and laypeople who want the pandemic to be over.”

Why, then, was the Revolutionary War crowd — Washington and his soldiers — able to listen to science, despite not even having a long track record of successful vaccines to look at? They did not see the scientists as their enemy. They and the scientists (primitive as their discipline was at the time) shared a common human enemy besides the pox — the British — and wanted the fiero of beating them; also, not doing so would be about as deadly as smallpox. They didn’t have their information filtered through Facebook — people vying for engagement — but through real people who shared their interests. Corny as it sounds, they cared about each other. They didn’t have their worst impulses supercharged, and their best ones dulled, by technology and late-stage capitalism.

Yes, crowd behavior is hard to predict. Yes, crowds can be massive. Yes, they can do terrible things. They’re like hurricanes, and just like hurricanes we’ve carelessly mutated them with technology; the Internet, where crowds have flocked, is where rational deliberation goes to die, and the fiero of owning the other side reigns supreme. This can make crowds especially scary.

Crowds have done things, and are doing things, that are about as close as we can get to universal definitions of both “good” and “evil” — both creating vaccines that end diseases and denying those same vaccines to the world. The point is that you shouldn’t love or fear crowds uncritically, whatever their track record may be. You should see them as what they are: groups of real humans that can have different motives, different environments, different outcomes.

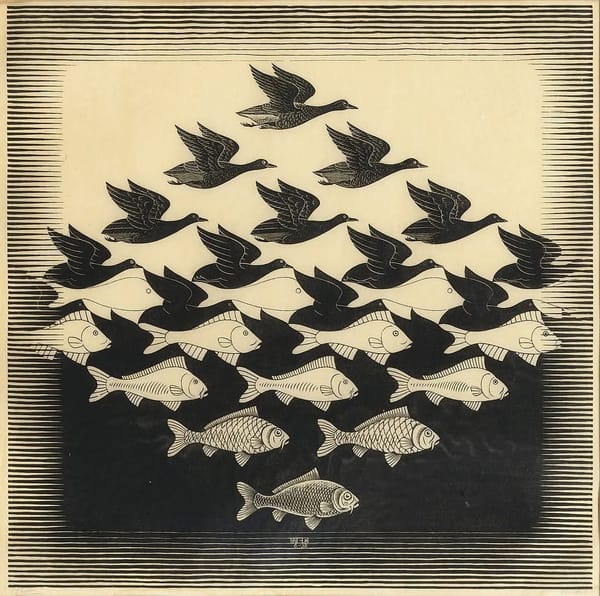

A crowd is a vine creeping skyward, a flock of birds going south, a natural process, a tendency. As with any natural process, it can be painted certain ways by us humans, but any connotations and baggage are also strictly for and by us humans. Vines creeping up brick walls are a sign of ruin and decay for no species but ours.

Context matters. Decision making processes matter. What is the crowd actually trying to do, and how? A crowd’s motivations, its environment, its internal methods for deliberating and making decisions — these mean everything.

We can see massive crowds and think about genocides, the Transatlantic slave trade, Chernobyl, and climate change. We can see them and think about civil rights movements, lunar landings, and canned food drives. Massive crowds aren’t going away; we have no choice but to cultivate their better angels.

Who Will Fact Check The Fact Checkers?

Structured mob decisions that use elections and expert opinions can be flawed, but unstructured kinds — those that fill the vacuum when the structured kinds go away — are worse.

Any group of people of whatever nature that comes together for any length of time for any purpose will inevitably structure itself in some fashion. The structure may be flexible; it may vary over time; it may evenly or unevenly distribute tasks, power and resources over the members of the group. But it will be formed regardless of the abilities, personalities, or intentions of the people involved. The very fact that we are individuals, with different talents, predispositions, and backgrounds makes this inevitable. Only if we refused to relate or interact on any basis whatsoever could we approximate structurelessness — and that is not the nature of a human group. This means that to strive for a structureless group is as useful, and as deceptive, as to aim at an "objective" news story, "value-free" social science, or a "free" economy. A "laissez faire" group is about as realistic as a "laissez faire" society; the idea becomes a smokescreen for the strong or the lucky to establish unquestioned hegemony over others.

— Dr. Jo Freeman, The Tyranny of Structurelessness

Groups can’t avoid biases and flaws. They have to try, however, or those biases and flaws will simply run amok. Put another way: group deliberation may go wrong, but leaving it unstructured means it almost certainly will go wrong.

The kind of science that should happen in the Food and Drug Administration, or the kind of justice that should happen in courtrooms, cannot happen in the unstructured way in which it happens on the Internet, where number of “likes” equals visibility equals truth. This is why Facebook’s lack of crackdown on white nationalism is so troubling; this is how you actually do end up with mass executions of marginalized groups that many, for their various reasons, think are “gross.”

That doesn’t mean we need to leave all mobs of regular people out of important decisions that should be based on data; on the contrary, part of Freeman’s point is that we need better ways of looping them in. For these giant decisions to be better, and not screw over most of the planet’s 8 billion people by default, we need a process for making those decisions that works.

An oligarchy of experts won’t fly. There have been times when they’ve behaved toward crowds much like the corporate elite, excessively fearing the influence of irrational mobs on their precious pursuit of universal truth. “Fear of the mob” is a philosophical “how should we decide what’s true” issue as much as a concrete “how should we decide what to do” one.

In a science studies book called Pandora’s Hope, Bruno Latour explains how this viewpoint was kickstarted by the classic “mind in a vat” thought experiment dreamt up by Rene Descartes of “I think, therefore I am” fame:

It is in order to avoid the inhuman crowd that you need to rely on another inhuman resource, the objective object untouched by human hands. To avoid the threat of a mob rule that would make everything lowly, monstrous, and inhuman, you have to depend on something that has no human origin, no trace of humanity…

To obtain such a contrast, we will imagine that there is a mind-in-a-vat totally disconnected from the world and which accesses it through only one narrow artificial conduit. This minimal link…will be enough to keep the world outside, to keep the mind informed, provided we later manage to rig up some absolute means of getting certainty back…this way, we will achieve our overarching agenda: to keep the crowds at bay.

As the rest of Pandora’s Hope explains, real science isn’t done like that. It never really was, and definitely isn’t anymore. It’s a huge global undertaking, and a profoundly human one, though it may study inhuman things. It requires the participation of tons of people to collect data and decide what research questions we ask next, even if not all of those people work in labs. Science needs mobs and mobs need science.

Scientists are really just another mob, after all, who gather evidence and knowledge about the natural world particularly well. You can replace “science” with other fields, like law and policymaking. Experts in these fields shouldn’t let laypeople steamroll over their work in destructive ways, but need laypeople for their work to be relevant.

Scientists aren’t perfect. Universities aren’t perfect, the CDC definitely isn’t perfect, and pharmaceutical companies are many light years away from perfect. This is all the more reason that their connection to laypeople should be stronger; they need oversight, and the rest of us need bodies like these — newer, better versions of them, that is — to inform our discussions with the (true) findings they make. Science needs laypeople, not just universities and corporations, to be stakeholders in the scientific process, and laypeople need access to accurate science to make good decisions. People should be able to learn about and look into findings without having to buy articles or tune into a profit-driven media outlet that will spin them.

The link between “normal mobs” and “science mobs” needs to look different. How can people and experts actually work together to make fact-based judgments that affect millions? How do we make sure the right people have the right facts at the right time, and aren’t acting on wild fantasies that harm everyone?

It is thanks to the unreasonable effectiveness of democracy — as in actual democratic decision-making that isn’t hopelessly warped, as it now is, by corporate interests and a money-driven Internet — that we needn’t even know exactly how, yet the solution is still tried and true. Democracy balances interests. It lets different mobs of people, each without the entire truth about the world, trust each other to provide their piece of the truth in good faith, for the purpose of making better decisions as a group. It lets them weather the ensuing disagreements about truth with the fact that, ultimately, they share common motivations and interests, such as not living on a fireball.

Those caveats about corporate interests and the Internet get in our way, but they don’t change the ultimate ‘how.’ They don’t change the fact that a leap of faith in the direction of democracy, despite being painted as rabid populism or socialism in many cases, is the solution. With real democracy, we don’t each need to know all of the ins and outs of everything — our court systems, the FDA, the DMV, the Coast Guard — in order to benefit from them and make good decisions about them.

We need the people we vote for to respond to these intuitions, and when necessary, consult experts that have the people’s interests at heart. We need a system that truly allows “1 person 1 vote,” and allows politicians on the ballot who we feel good about spending those votes on — politicians who combine our core interests with the advice of experts, as Washington did.

Of course, as long as the Internet — the place where people access “science” — works the way it does, this will be an uphill battle at best and a fool’s errand at worst. We will continue to have random social media stars and bought-off politicians getting the final say in how we address highly technical issues like pandemics.

If this “leap of faith in democracy” sounds overly simple, that’s because it is. It’s pure common sense, and common sense doesn’t drive clicks on the Internet. Since the Internet is where we all are, we’re not following common sense. We’re not pressuring the government to get money out of politics or any number of other things we need to do. Such things don’t merit online communities that can throw their weight around. Not just yet. But it’s starting to happen, even in places that weren’t designed for this, even if only out of necessity.

A Tangle Of Mobs In A Series Of Tubes

Our species is a tangle of mobs. Some mobs like each other; some chafe against, but begrudgingly accept, each other’s presence; some hate each other’s guts. If you zoom out enough, though, no single alliance or conflict among them looks very prominent or permanent.

You do, however, see something interesting happening to the whole tangle. It’s getting, for lack of a better word, tanglier. The results of a given mob’s decisions — whether those decisions are in service of a feud with another mob, or the mob’s own comfort, or whatever — are lasting longer. Spreading farther. Casting more intense shadows over individual members.

With modern medicine, we live longer. With the Internet and air travel being commonplace, we connect more and pollute more. We get to make more decisions; each decision makes more things happen. How does the saying go? We have godlike technology, medieval institutions, and paleolithic emotions. Wherever you sit on the Luddite spectrum — whether you think we should abandon electricity or upload our brains to the cloud ASAP — you cannot deny that this is the current state we’re in, the reality of the situation humanity has created for itself.

The 20th century was the opening act of this critical point of global tangliness; the 21st century is the main show. The tangle has reached a point of never-before-seen acceleration in the progress of science and technology. The Internet, for better or worse, stands at stage center. And while it’s global, most of those who shaped it grew up in America. This country in the 1990s was a place where capitalism, individualism, and entertainment had not just reigned supreme for centuries, but recently triumphed in the Cold War. Our Ally McBeals and our Gordon Gekkos welcomed the Internet with open arms.

The Internet became about fun because fun — excitement, fantasy — drives engagement, and engagement, be it eyeballs watching, ears listening, mice clicking, or thumbs scrolling, is what drives profit. It drives people tapping ads.

When enough of what’s around you becomes a fantasy, attempts to discover reality therein become futile. It’s like the Truman Show or the Matrix; you have to venture outside the bubble to see it for what it is. Otherwise, you run into façades and artifice at every turn. You constantly face people trying to make a buck from you. It’s like trying to get a sense of your true reflection in a funhouse.

Despite this, we have carved our filter bubbles and settled in. We’ve chosen who and what we listen to. We’ve done so with gusto while doing little to ensure that the sources of what we hear in them are trustworthy. We are not as naive as it may seem, just lazy. It was the default choice to let this happen, and we chose that, and we’re seeing the consequences. The collision of the Internet and human mobs, with no real oversight beyond “the invisible hand of the market,” has been electrifying to watch and be a part of. It has made the Internet wild and fun. It has also been a train wreck of epic proportions.

Like climate change, it’s a meta-disaster — a disaster that’s polluting our resources (in the Internet’s case, attentional and cognitive) and making many other disasters worse as a result. It’s a disaster that reverberates, sending waves into other issues. It is one that we have to stop gawking at and do something about. As Jenny Odell put it in How To Do Nothing, “in a time that demands action, distraction appears to be a life-and-death matter.”

We have let our news and information ecosystems fail, and put the burden on individuals to make sense of the mess, as Americans do with everything. Pure individualism won’t cut it anymore; every human’s actions affect the climate. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. With the mobs’ increasing tangliness, there are more and more situations where “we’re all in this together” starts to apply. It’s the same with the Internet: we have not collectively ensured that we have good, clean water coming from the taps of our shiny information fountains. We have simply made the faucets — Twitter and Reddit and the like — infinitely more fun than the process of validating what comes out of them. The laws and politics of agencies like the FCC is, comparatively, a snooze.

Because farce and tragedy drive clicks, this Internet pumps gas into our feuds more than our alliances. The loudest and most outrageous claims get extra exposure. Such claims are also (because they’re outrageous) disproportionately likely to be evil or wrong. The stories that many mobs in the tangle are telling themselves, then, are growing increasingly unhinged, fantastical, and destructive. This online environment has let extremism and bad scientific decisions flourish, bleeding out into the real world. Angry, groupthink-possessed crowds are creating dystopias both mundane and terrifying. The rest of us argue about the extremism online, effectively doing nothing to stop it. Crazier and crazier ideologies evolve and mutate out there, “waiting in the bullpen” for their time to shine, as writer Anne Helen Petersen has put it.

The motivation behind writing this was a meeting of two ideas that, independently, can seem intuitive, but create thorny pockets of conflict when you put them together.

One is that, yes, it can be scary when a very large mass of people chooses to act on some collective emotion. On the other hand, it is both difficult and necessary to give large numbers of people a voice on things that affect large numbers of people. Doing so effectively and fairly, and protecting ourselves from tyrannical mobs that do so destructively and poorly, is about as close to an intrinsically good goal as we have.

We have no choice but to engage in certain big, global renegotiations. It’s a bridge we have to cross. It is becoming necessary that we address certain problems in real, actual, well-intentioned-if-imperfect ways, rather than waiting to get them perfectly, exactly, 100% right.

What do I mean by “renegotiations?” The time draws near when we’ll have to do things about large issues like sustainability and authoritarianism and justice and labor relations in grassroots, bottom-up ways. The signs are already here. Look at Extinction Rebellion, the Capitol riots, the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, the “Great Resignation.” These conversations are going to happen one way or another, and are picking up the pace. We need to decide on ways of holding accountable the people who have disproportionately caused our biggest problems, and ways of preventing the same kinds of problems from happening down the line.

Such negotiations can’t continue to happen with little to no input from the millions of people they affect, or with bad and ill-informed input from them.

Crowdsourcing Democracy

They say there’s nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come. I would put it a different way, since “idea” has the ring of something automatically good and just, and bad ideas have been powerful before. There is nothing more powerful than a crowd sharing a fantasy.

Technology’s ability to amplify what we collectively imagine has little to do with how sensory and vivid the technology is. It has everything to do with how much it connects us, emotionally and socially, to each other, and how it harnesses crowd feelings like flow and fiero. Facebook posts consisting only of text are enabling many fantasies far more vivid than anything virtual reality has to offer.

You’ve probably heard about the original War of the Worlds broadcast in the 1930s — yes, a few people tuned in and thought aliens were really attacking — but that event itself was blown entirely out of proportion, because it would spark intrigue and make headlines, and it did. Countless stations and newspapers ran fabricated stories about a “mass panic.”

Using communication technology to help solve our problems with communication technology may sound obviously flawed, but only in the same way that some scary crowds can scare people off all crowds. It can be tempting to dismiss technology as an unnecessary and too-dangerous part of any political solution to our problems. Smartphone apps being used for voting, for example, involve cryptography challenges that some would (rightly) not trust our government to solve, whatever the idea’s merits.

More commonly, the technology is just bad. It often feels like, even if they haven’t outright betrayed us (and some have, like certain law enforcement agencies and energy companies) our public institutions have become hopelessly outdated and Kafkaesque, or entirely unusable. Only a few countries, like Estonia, have really bucked this trend.

We increasingly don’t even want to engage with any kind of institution, political or otherwise, because of the quality we’ve come to expect, and the fun we’ve been able to experience, in the apps we use in our daily lives.

It’s precisely because technology can harness our flow and fiero so well that, to the extent that it can do that for good ends, we should use it. We expect better, which means we can do better. What if, for once, we used technology to share a fantasy where large groups of people made good decisions with facts?

Just because it’s hard and apps can be hacked doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try something beyond the crumbling public infrastructure we have, or infrastructure that only the rich get to enjoy.

We can and should update our medieval institutions. The concept of “an institution” is not inherently flawed, or at odds with technology, or needing to stay medieval. We just need to make institutions better and more accountable. We need “insurance” for each other, whether about healthcare or true information or safe food, that we all pay into, and that isn’t like the private insurance rackets we have that’ll turn against us on a whim.

We used to do this. We used to craft institutions like PBS and NPR that we agreed we would pay for, and then be able to benefit from and trust, because it was us, a government for and by the people, bringing them into being, not some shadowy Big Tech company.

We need a space for high-quality information that has this mutual accountability, and ideally some kind of engaging structure around it — a way for people to feel both personally invested in the process of getting informed, and fully able to access what they want in the first place. We need something like a Wikipedia, a new cable network, a 411 line, all rolled into one, except better than all of those.

Masses of non-experts on a given issue need to be able to hear — and experts able to give — solid, well-supported facts on current events and scientific issues in an unadulterated corner of the Internet. Most of the Internet is not the place for that, but there can be a place if we make one.

Any such alternative — any kind of democratic, not-profit-centric control people try to exert over something — will be branded “socialist,” and therefore will be hard to implement. It’s happened to things like education, libraries, the post office, and public broadcasting. Con men and demagogues like Reagan and Bush and Trump have found ways to gut public services that their corporate friends don’t like, selling them for scrap, making information literacy suffer, convincing America they never wanted it.

We can’t fall prey to this mentality anymore. Taxes may go to things we don’t like, but the fundamental idea of taxes — paying together into things we democratically decide we want — is good if we make it good. We can keep our beloved, insane sites, table-flipping and all, and still create a separate space, managed by the people, where common sense and sanity let us make good decisions. It will be in service of long-term, widespread “profit,” rather than just short-term, monetary kinds concentrated in a few hands. We can take the goodwill people have, the fun we have in sharing knowledge, and actually put it to work.

We can use it to have large-scale conversations that aren’t currently happening. We can use it to welcome the voices most informed about the technical details of a given conversation instead of the most deranged ones. It will “average out” our extreme and intolerant impulses so that those impulses don’t make it past the vast majority who don’t want them.

We know things about crowds and groupthink, and we can use them in designing this space. We have countless case studies and countless pages of historical records showing how they work. We can do all of this not in a creepy, secretive, paternalistic way, but an open, transparent way. Others — sociologists, psychologists, political scientists — have thought about how something like this would work far more than I have, and keeping with its spirit, we should listen to people like them the most on how we should construct it. The rest of us need the political initiative to create it.

As starting points, I can offer examples and tasters of how people come together to construct solutions beyond vanilla democracy and simple majority-rules voting; if I can find this much with some Googling, America can do much better.

One — maybe the simplest possible one — is to look at the “surprisingly popular” answer of a voted-on question. That is, by also exposing what people think the “uninformed” masses will say, it hints at what the true answer actually is. There are countless other methods of getting a “mastermind” out of people; the Internet-enabled ones quickly become more interesting.

Sites like Twitter and Reddit, despite being relatively bad for public debate, are amazing at aggregating the best of a given type of content, be it funny memes or helpful tips about anything from home improvement to pet care. This could be done for more technical content, too. It already has, to a large extent, by sites like StackOverflow.

Waze, a traffic app, uses crowd information to inform drivers about road conditions. TraffickCam uses a database of photos taken of hotel rooms to help catch human traffickers. Freerice, a vocabulary quiz game, donates rice for every question answered. EyeWire is a game that lets users identify large volumes of mouse neurons in 3D scans that neuroscientists took. People just like to share; that sharing can be gamified.

It can also happen out of sheer need. People have started bootstrapping serious pandemic-related information-sharing spaces on existing platforms like Facebook — ones really not suited for it — due to the climate of doubt. When people care, they find ways.

What if we didn’t have to rely on random people on Facebook, or the ways that Facebook chooses to surface information? What if we had a Wikipedia-like social network of people beholden only to the users, who would share technical insight on important problems — scientists, journalists, experts in all fields? What if the simple “fiero” of winning an argument or knowing more than the other guy wasn’t the goal, but clear communication and coming to good, sound, accurate conclusions instead?

These things happen, after all, when people share interests and level with each other.

Sick Note: You seem to have a lot of compassion for people who are resistant to vaccines. Is it hard to maintain empathy for the people you're helping?

Sharon: Sometimes, it is. Some people are unreachable & are like those parents ranting at school board meetings in south and central Florida. But a lot of people can be persuaded if we are willing to get creative & be persistent. People let down their walls when they're talking to someone who comes off as truly earnest to them, & not motivated by scoring points for partisan politics. I do not like the idea of giving up on people, not even older people that some would write off as a lost cause. Death is very final, & it's the snuffing out of possibilities. People can grow & change & now we'll never see the full potential within some of these people we have lost.

— Libby Watson, Sick Note (emphasis mine)

There is a balance to strike here; we have to communicate with people, but not focus so much on “empathy” that we waste time entertaining too many ridiculous ideas. We have to guard against extremism in crowds, not just try to make all the individual extremists “see the light.”

We don’t have to debunk every insane conspiracy theory about COVID and 5G towers or Ivermectin suppression; we just need to get accurate information out there. We have to make it possible for people to dig into the questions they’re interested in, and get accurate answers. If more people had this — if they knew, historically, how deep the anti-science rabbit hole goes beyond Ivermectin and Dr. Oz — they might think twice about believing in the next snake oil.

With increasing frequency, mobs need to be able to trust other mobs. We need ways of make this possible, and ideally easy. We need mobs to be able to enact real justice, do real science, and let both processes be informed by the other. This can’t happen when mobs primarily fear each other and live in doubt of each other, as many currently do on the Internet.

We need good information flowing from our information taps, and no one will simply do this for us. No one will save us here. Some will even fight us on this. No one will make it happen for us except ourselves.

Epilogue: What Do I Know?

You may wonder: what’s my agenda? What’s my angle here? Do I have ulterior motives for writing this? Not really. I don’t want to live in hellworld. It’s not that deep.

But do I have the moral authority to write this? Am I not a hypocrite in some ways? To this I say: you can believe rationality has a fundamental role to play in our lives — that it can emerge from mobs — and also be a human who does irrational things. Plenty of people well-versed in mental health issues still self-medicate with legal substances like caffeine, alcohol, or entertainment in ways they know to be inferior to meditation, therapy, and exercise. They can still endorse the latter professionally and be right.

But where does my logical authority to write this come from? From a technical standpoint, why trust me at all? A few college classes? Reading some articles? Being terminally online? What do I really know about online mobs? That’s the most fair question. But if there is a subject I can talk about more knowledgeably than most, it’s learning.

I’ve studied learning for a long time. People associate learning with reading and repetitive practice, with kill and drill, and not so much the ways it can be immersive and engaging, like in video game tutorials. They also tend to forget that that’s just one part. It’s hugely dependent on how and why you trust your people and your sources, and what’s motivating you to learn in the first place.

We have to make this a regular, institutional thing. We have to make it so it’s not just a few John Oliver types teaching us about things, not just a horde of schmucks writing essays and making “explainer videos,” but all of us, in little ways, all the time, for ourselves.

On a global scale we have to make learning motivational and trustworthy enough for us to make good collective decisions with what we learn. We have to do this not just for the foundational things we learn in school, but for all the little things we learn every day, in the news and elsewhere, about what’s happening in the world and why.

We have a duty here. We need to put our different kinds of knowledge, whatever they may be for us individually, toward a more trust-filled world, a world more balanced between fact and fantasy than the current one. I think we can, not just because history shows it, but because sooner or later we will have to. People abhor tyranny, so some form of democracy is here to stay; people demand connection, so some form of the Internet is here to stay.

Our fate rests on how a very large tangle of mobs chooses to act. We have to be the change we want to see in the mobs we’re a part of, and remember at the same time that this isn’t always enough in such a big tangle. Often, we need other people, in other mobs, to want to do the same.