You’re the soup and the one stirring it

Models of the mind and what they do to morality

I.

What if, when young people seem performatively woke or puritanical or too eager to “cancel,” it has a lot less to do with morality than we assume and a lot more to do with bad models of the mind?

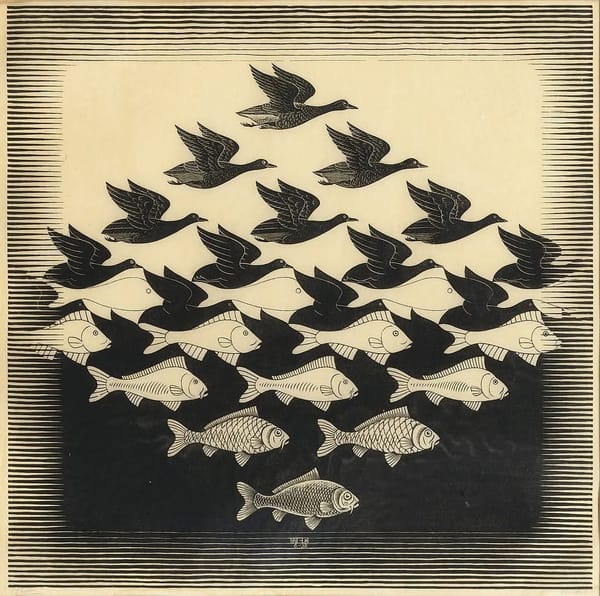

The brain is not a simple machine that functions in a “right” or “wrong” state at any given moment. It may be, in one sense, a chemical soup, but not one that you’re standing over and stirring. You’re sitting in the soup, and in this way you’re part of the soup. You are the soup.

When things happen to the soup, they also happen to you: your personality, behavior, thought patterns, memories. The reverse is true. Your behaviors and desires interact with your mental quirks and pathologies in both directions. Bundled together, all of these are “you.”

This can be obscured from us by the way we think about the brain. Thinking of the soup as some boring mechanistic thing, external to us — a black box that we can only stir through chemical and surgical intervention — makes us forget that in reality, interrogating what we think, and practicing thinking differently, will change the soup. Therapy, meditation, psychoanalysis. The soup can change us and we can change the soup, positively and permanently, by commanding it to swirl in certain ways with sustained regularity.

II.

People with an inaccurate model of the mind make discussions about mental illness exhausting. You find a surplus of people who only ever want to trace “problematic” behaviors and desires down to specific lines and words and letters in the DSM, and for the express purpose of condemning and erasing them. You find a drought of people doing something significantly more productive: investigating our behaviors and innermost desires, grabbing them like threads, using them to help us untangle pathologies behind them, some of which you find are not pathologies at all but healthy adaptations to unhealthy circumstances.

Correcting this asymmetry is not everybody’s equal responsibility. Not everyone needs a Ph.D. in neuropsychology, or needs to make a “teaching moment” of any discussion of the brain no matter how lighthearted. We’re all going to mess up when talking about this sometimes. The fundamental attribution error makes sure of it. This is where we wrongly identify a person’s built-in qualities as having more of an impact on their behavior than temporary circumstances. When I messed up mysterious forces were conspiring against me; when that guy messed up it was because he sucks.

To get around this we need only answer the following: how much legroom, how much compassion, do we give each other to be wrong about it? How much should we expect a reasonable person to know? These may seem thorny and unpleasant, but their alternative is much worse: making everyone know everything. Throwing out science as a profession and making everybody answer a much larger set of much more complicated questions. How are the material realities of our lives helping or harming our mental health? What are the best ways for us to intervene and treat ourselves? How much does mental illness factor into crime?

Be grateful that some people like to nerd out about these, discover things about them, meticulously collect data about them, more than you ever will. Thank your lucky stars that you need only worry about how much legroom to give others when talking about it, and how much it’s on you to act on the results. (The short answer, in both cases, is “some.”)

There’s a reason it’s worth doing science and worth letting some people do it a lot. For this reason to apply, though, those of us not in the lab need to make a world where it’s worth it. We need to follow through with the well-established results; we need to make sure all can buy into the research, and all can benefit from it, and understand it just enough to talk about it without it being exhausting. That process of getting buy-in may feel a bit long-term, but it’s the only way out, the only way to make people want to reason more correctly and compassionately about mental health. Otherwise it’s just eggheads making other eggheads richer, leaving everyone else to shun science and obsess over crystals and essential oils forever.

III.

Young people have, in their defense, seen something interesting happen to science that makes this understandable. It went from being about the public and beneficial things we grew up with — schools, energy grids, satellites, the Internet — to money pits like Theranos. We grew up with the benefits of science, but the world unfolding in front of us expresses little but disdain for it.

We publicly paid into COVID vaccines only to have (1) a few companies start charging for it a few years later and (2) a bunch of people not even want the vaccines in the first place. We’re products of a Tomorrowland judging it on its recent failures, which themselves are the product not of science alone, but of its recent alliance with financial services, short-term wins, and con artistry. Americans of many ages, and especially younger ones, have reasons for thinking “science” is something it isn’t and taking it for granted. This leaves us at a crossroads between having enormous amounts of scientific data available to us and unprecedented amounts of doubt cast on it.

I’ve seen the surging interest in astrology and witchcraft and tarot and personality types and “reality shifting” and the “divine feminine” (a rebranded version of “women should be homemakers”). Our institutions simply haven’t given young people a scientific, future-facing narrative with any a sense of hope or trust to latch onto; they’ve given prescriptions and restrictions and a planet looking absurdly comfortable in some places and absurdly like a dumpster fire in others. I get the backlash.

But people will continue asking questions. Sometimes those questions will irk large corporations and sometimes they won’t; they will press on either way. They will continue to do the things that answer them most effectively: controlling variables, experimenting, collecting data. Science will continue to be a part — not the whole, but a part — of whatever solution gets us out of our messes involving COVID and climate and mental health. It’s not just another belief system. It’s precisely the opposite: a skepticism system, used for good or bad ends, by human beings.

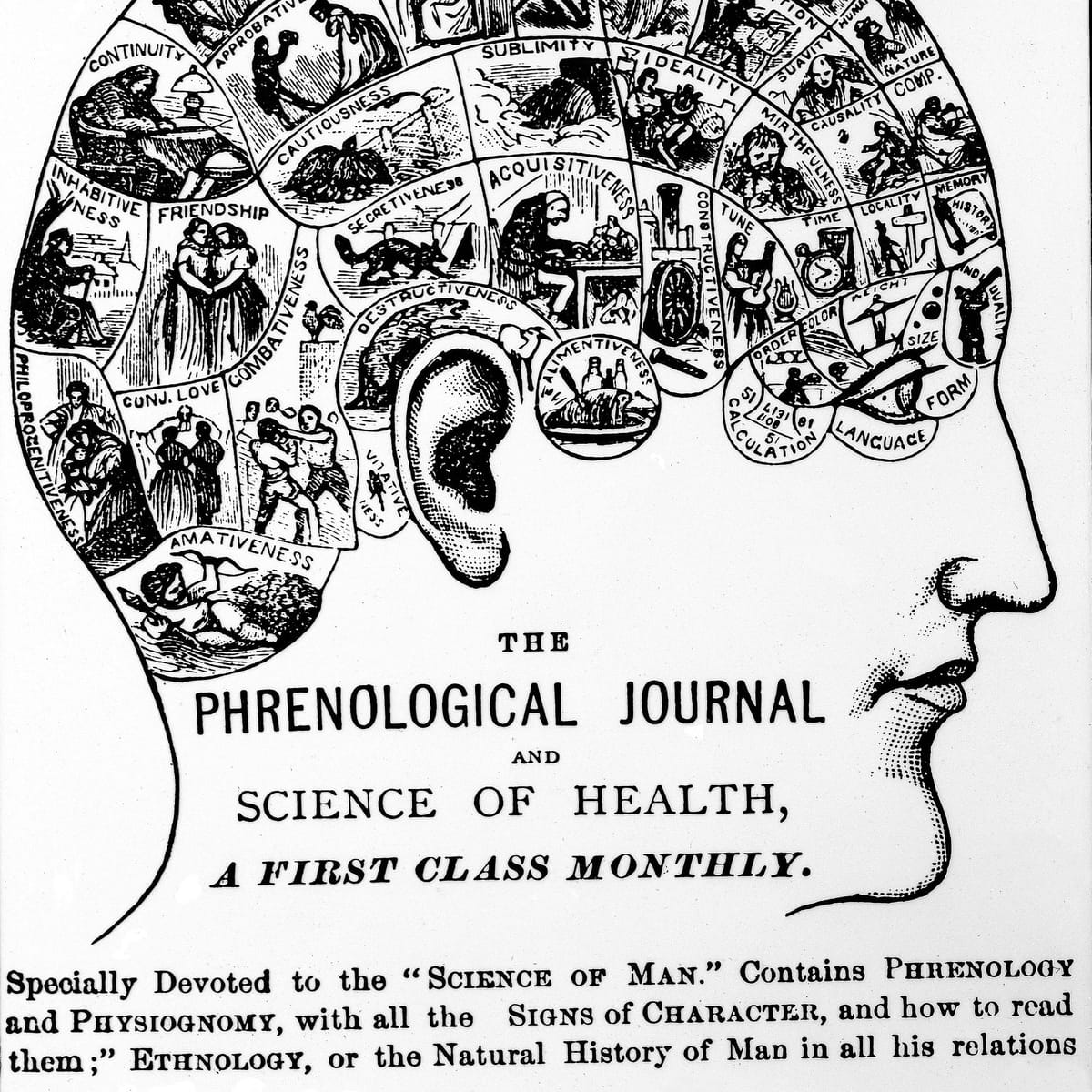

Understanding ourselves, physically and cognitively and emotionally, is easily one of the best uses of it, which brings us back around to the tweet from the beginning. Science relies on throwing inaccurate theories out just as much as bringing new theories in. We need to throw off models of our brains that simply don’t work. The better we truly understand our brain’s capabilities and limits, the ins and outs and nooks and crannies, the better we can work around them. We can dole out compassion instead of just punishment when those limits are reached.

IV.

I know most people do understand this. Most are truly on board with science and feel powerless to do much about the systemic issues that grind its ability to help us to a halt. Most know that real science, even if trapped in evil, banal, dreary, robotic cages much of the time, is an extremely human task, a way of knowing more about our world. But it can be hard for many — it’s often hard for me — to envision how we’ll continue it, and continue talking about it, in a way that benefits us, given the entities that control so many scientific resources.

This is precisely why the shift in perspective endorsed by Moskowitz needs to happen! This frustration we have, the inability to see a path toward having a collective say in science — that’s based on a good desire. It can make us sad, even depressed, which is seen as pathological, but the roots of it, the roots of wanting an outlet for our curiosity, are not to be pathologized.

One often needs more than antidepressants to address such desires, such self-actualizing needs. You cannot “Lexapro away” certain questions and hopes people have. When people bash antidepressants, it’s often based on good intentions of this kind; it’s not really the antidepressants people find offensive, but rather the particular view of the psyche that they hold up like a crutch, a framework that offers little in the way of the proactive, the healing, the regenerative, the awe-inspiring, mostly just “take this to not feel so bad.” The dissatisfaction with this model is broad and diffuse, a smog that large pharmaceutical companies put out, an externality of how they do business. It’s tantalizing and depressing how close yet how far the solution is: give them their say in science back.

Make scientific infrastructure and resources publicly funded. Do research on things people want. Use the results to improve things in ways everybody benefits from for decades down the line because everybody paid into it. I know how kumbaya it sounds; I’m a broken record about saying it. But it pays to not forget it and not fall prey to contrarian, authoritarian, tech-bro sensibilities on this one. Democracy is the worst form of government except for all the other ones; the democracy demon is out of Pandora’s box and it’s not going back in.

V.

My city decided decades ago that plowing snow from the roads is an effort that everyone with property taxes ought to pay into. Nearby Milwaukee was the first in 1862. To this day, no sane person questions that it’s the smart thing to do.

There is no reason not treat more collective efforts this way, starting with science. And then high speed rail, and healthcare, and energy grid improvements, and other no-brainers. There are things that hordes of young people would be excited to help out with: potential sources of community, reasons to imagine a better (or at least less hellish) future. Instant political wins.

Lawmakers, and many others, have blinders on. They operate on — even if they don’t believe! — utterly broken models of the brain, seeing them as top-down contraptions whose “malfunctions” must be scorned in a puritan way, never understood or studied or empathized with.

Dropping those blinders doesn’t mean throwing out the notion of doing science on the mind and brain altogether. This is a natural part of the scientific process. You ditch frameworks that don’t describe reality in order to find ones that do. Then you can use the ones that work to bring dope new things into reality.

You’re literally helping science happen when you help people drop bad ways of seeing things that don’t work. The more people in a society believe a wrong thing, the less likely it is that anyone in that society is going to question it and find the actual truth about it.

There’s always more to the story of how the brain works. There’s a uniquely reliable method for finding out what it is. But to use it, we need to abandon certain bad models, models that make morality deceptively simple, and have the courage to pull new threads.