The electric banana

The story that definitely kind of happened

1.

Here’s what I was told: five monkeys are in a room with a ladder. Suspended over the ladder is a banana. Any monkey who tries to touch it gets shocked. They all quickly learn to not touch it.

One by one, researchers replace the monkeys. Each time a new monkey tries to touch the banana, the other monkeys drag that monkey away, which teaches them not to touch it. After five replacements, no original monkeys are left in the room. All continue to avoid the banana. All continue to stop each other from touching it, even after the researchers un-electrify it.

A thought-provoking parable. The message is simple and true: social rules should be questioned, not followed blindly, because situations can and do change, maybe not by researchers but by human events. There’s a sense in which it doesn’t really matter if the experiment happened this way. The point stands.

But like, did it? And if not, where’d the story come from?

I found articles parroting the original. I found articles saying “nope, made up, didn’t happen.” Most bafflingly, I found articles that linked to the original text of a real study from 1966 on which it appears to be based, but with intriguing differences, and still they said “nope, didn’t happen.”

Primary sources. Read them while you can.

2.

So here’s what happened.

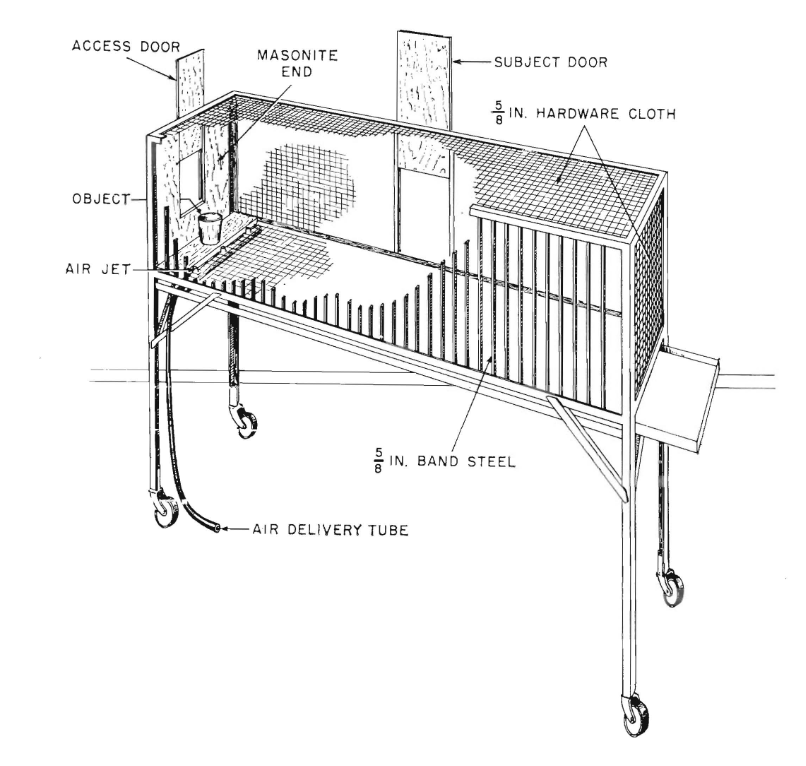

A monkey would get put in a chamber with a kitchen utensil. In the control condition, there was no penalty for touching it. Touching it in the test condition earned a blast of air, which you’ll know is arguably more effective than electrocution if you’ve ever been to the eye doctor. Lowkey sucks.

Another monkey would get put in the chamber with the first one. The air blasts would be turned off. The new monkey would investigate the thing and the researchers would note what the first monkey did.

The males and females behaved differently. The males deterred their new friends; the females didn’t. Only one male dragged his new friend away. Most of the time they just gave the new monkey a look—wouldn’t do that if I were you—and that was enough. The females would initially avoid the object and not interfere. They sat in the corner and watched as the other monkey received no penalty. By observing, they lost their fear responses. They went back to touching the thing.

3.

Was the study designed well enough for this to tell us anything? Are monkey gender differences transferrable enough for this to tell us anything? I don’t know. And that’s the thing: it’s easier for us to draw direct, digestible conclusions from the fake story than the real one.

But there is one you can draw from the real one. There is something transferrable. Real behavior is not as uniform and unchanging as we pretend it is, as simplistic and doomed as our stories tell us it is. The Dawn of Everything by Graeber and Wengrow shows this in great detail. Early human societies experimented with hierarchy and social organization in ways totally glossed over by the narratives of world history we’re taught. “Little egalitarian bands evolve into big tyrannical cities. That’s just where we had to end up.” That’s just not the truth, and the areas of land, the time windows, in which it’s gone that way are narrower and fewer than we think. We’re just biased because we’re in one of them.

The truth, though more complex, is just better. The lessons you can get from it take more work, but they’re better. If you’ve already let wool be pulled over your eyes, and that’s what you think the truth is, then the truth will not feel freeing, empowering, satisfying, or comforting. But it is, once you get used to it. And much more so than the feeling of having the wool rudely yanked off, as it inevitably will be.