A tour of the shadow factory

I

You did something you weren't feeling especially driven or excited to do, but a past version of you figured it was good and necessary. You changed a behavioral pattern that served you once, but no longer does. You were feeling bad, but had to shop for food; when a friendly cashier asked you how’s it going, you didn't tell them the whole story.

When you do these things: are you being inauthentic? Are you pretending to be someone you're not? Yes. Good. Are they examples of callously pretending or nobly becoming? Hot take: a distinction without a difference.

II

It's tempting to imagine a difference. The word “becoming” connotes alignment. “Pretending” connotes artifice, transience, mere usefulness. This is being lulled by language.

Alignment with what? Your self is not a rail you can grab onto, guiding you to becoming instead of pretending. Your self is the thing looking for the rail. We say phrases like “You haven’t been yourself lately” and “I don’t feel like myself.” But the only way we sense these things is when something's off, wrong, pathological. We “feel like ourselves” when we’re confident, automatic, frictionless. The more you try to feel the self, digging down to the root, the less you can. If you know, you know.

Alignment doesn't come from becoming more than pretending, but from paying attention to what kind of person your pretending and becoming is making you. The real consequences, not the abstract justifications. Because we're constantly called to do both. We’re constantly called to be better than we may want to be, to do necessary and helpful things regardless of how we feel, which may sometimes involve getting through them by pretending we’re doing better than we are. And we’re constantly called to be fully ourselves, lest we repress, and repressing harms ourselves and those around us. We adapt; over time our becoming becomes different.

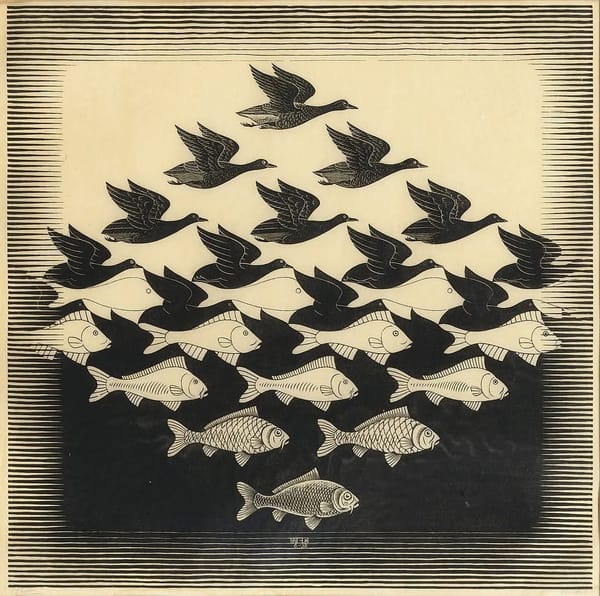

The original Jungian idea of creating shadow is the rejection and suppression of parts of ourselves. That’s a little strong. What happens in the trenches it that we stash pieces of ourselves away. This is the human condition; sometimes you grow to care about others more than yourself, or learn how to be a bro to future-you. You grow up. Sending out the light we need to send out sometimes means creating bits of shadow. Sometimes it's fine; sometimes you just need to shine the light back inward, too – integration, as the Jungians call it.

You can still guide and steer yourself. MGMT told us we were fated to pretend, and that's okay. As Solange puts it: fall in your ways, so you can wake up and rise. As Kendrick puts it: introduce them to that light, hit them strictly with that fire. We're all called, in a world like this one, to forgive the unforgivable and forget the unforgettable, to change ourselves in response to its changes, to be shadow factories and not let it discourage us too much.

III

David Foster Wallace crafts open-world role playing games where each encounter leaves you a little less insane, a little more whole. Nabokov pushes you down winding paths in dark and shining caverns filled with gems of language. McCarthy, Steinbeck, and Hemingway lay out a Zion National Park of sentences before you, harsh and stunning, where the marrow of life is spread across the pages.

Clarice Lispector walks up to you, looks at you funny, and socks you in the mouth. As you feel your lip, she grabs your mind by two corners and yanks, leaving it askew in a mathematically impossible way. She walks away.

IV

Everything we do exposes nerves. Everything to some extent peels back what's around them, touches them, consumes them. Our refuges from the demands of time demand more time. Do enough of the right things, however, and in the right ways, and you can restore them at the same time, sinking into the act of exposing them. There are things that, in other words, don't inherently degrade the nerves like others do – ways like music: when it hits you, you feel no pain. I mix these things in with the scrolling and stress snacking – I mix in yard work, exercise, pub trivia on nights when I want to stay in, heavy reading.

In any of these, even reading, you still run risks. You can pinch nerves. Injury by the yard you care for; pulling a muscle; saying something wrong and immediately knowing it; stumbling across The Passion According to G. H. by Lispector, and getting socked in the mouth, and seeing things committed to paper that you didn’t think could be, which re-expose deep nerves and set them ablaze. If you let them, these events can have the wrong effect – deadening you, hardening a shell that neither light nor shadow can punch through. These days the nerves are primed and buzzing before you even start: Ukraine and Russia, Israel and Palestine, police and protestors, viruses and anti-vaxxers, wildfires and lungs, AI and humans.

We're in a lifeboat. At any given time, some have to fish, and others have to sleep, and at inopportune moments, too many may simultaneously fail to muster the will to carry out their (increasingly haphazard) obligations to pretend/become. When that ability runs out, as it does – when we biological things run up against biological limits – what then? What happens when, as Lispector puts it, the shifting sands under our structures, our monuments to inattentive pretending and becoming, move one grain too many, and the thing comes tumbling, and the massive weight of reality falls onto the immovable needle of the present?

Lispector, for her part, takes the hand of the reader. More broadly, we take turns. Whether the lifeboat will get back to shore is immaterial; the best we can do in the situation is get better at taking turns, with our pretending and becoming, with the task of keeping our shadow structures up to code – and with the rest our bodies need from both.