If we wanted to, we would

1.

It varies in close relationships; beyond those, we expect too little from each other. We live in an art show where most of us pace around, looking at stuff. It may affect us; we may cry or rejoice; but much of it is so brutal and grotesque that it demands to be acted on, not looked at, and we don't. All this personal autonomy we have; since acquiring it has meant snipping every string of expectation and responsibility between each other, we don't use it. We're too alienated to use it in the ways that really matter. If we wanted to, we would.

2.

A set of graphs has been making the rounds. Young men and women are diverging politically. Humans, not just guys, want to feel useful, valued, needed; when we expect too little from each other, when so much is autonomous, we don't get that; the bitterness that results, the forced participation in an economy untethered from the real needs of your community, is more pronounced, more regressive, when it comes out of men, not as trained in dealing with emotion; the Internet supercharges this difference. All of this was explained in full detail by bell hooks back in 2005. The trend is now accelerating.

A teenage boy gripes that a girl can easily gain a lucrative online following by being attractive. His peers don't typically tell him that the call is coming from inside the house, that it's guys at large who create the demand for her content in the first place. They tend to tell him: "Exactly right, little bro." The reward given to women at large for bearing the brunt of this whipped-up, misdirected bitterness is an assault on their reproductive freedom. The graphs are not hard to understand.

It's not that women no longer have any use for men. That use is different because times are different. Mammoths are extinct. The challenge before us now is this art gallery, and all these exhibits no one is acting on; a world where the least deserving people pay the most for the crimes of others; an economy that presents a false choice between exploitation and marginalization. The gargantuan task of creating a third choice, a just world, a cleaned-up art gallery, juxtaposed with our amped-up thirst for being useful, is like being handed a gallon of water after a drought. If we drink none at all, we die; if we try to drink it all alone, we die; if we piddle around in between, finding proxies in our armies and corporations and Call of Duty lobbies, we die particularly slowly. We have to expect more from each other. If we wanted to, we would.

3.

To read is to not have anything expected of you. That's a big part of why I love it. I'm reading Snow Crash and there's absolutely no obligation to sift what makes it wise and prophetic from what makes it dumb and fun. It's all wrapped up together; you read it; it's a good time. And by osmosis, you learn a lot anyway. Code and language: is it fleeting and ephemeral, especially now as it aims for smaller chunks of our attention? Or permanent, out there on real servers and disks, copied and persisted with increasing ease? Words: abstract and weightless, or can they infect people, viruses in the form of myth, changing minds and spurring action?

Life cannot be all reading; sometimes you have to sift. Those graphs I linked to: do they represent something real, or sensationalism via statistics? Regarding expecting more from each other: which ways to do it are effective? New health fad X, new conspiracy theory Y, parenting technique Z: grain of truth or psychobabble, wishful thinking, a marketing ploy? That band you've started to like, whose sound is 100% lifted from another time, whose whole style is cloyingly derivative: they're so good, though. Do you look past it? Are you writing right now because it’s comfortable, a little escape, or because you have something to say? Sifting, sifting, sifting. To be productive, to make progress, you have to sift.

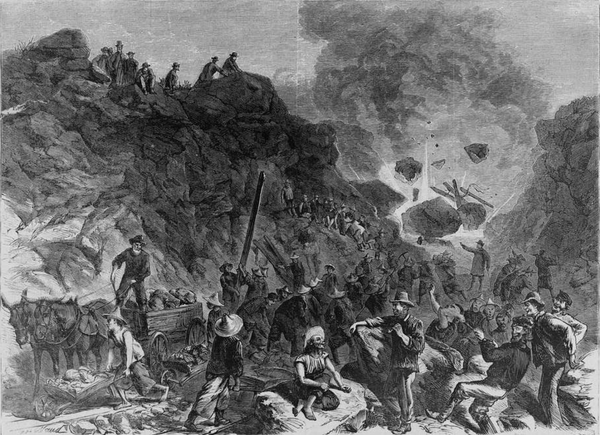

A few of our ancestors went down to the river to sift for gold. They couldn’t stop. Like the Yelnats family from Holes, they got us all cursed to a lifetime of doing the same. The need to sift is so great that you no longer need to be crazy to wonder how much of something is real or fake, though you certainly do run the risk of going crazy by sifting for too long. The opportunities to stand in the river, holding our pan to the side, enjoying the scene, are fewer. We notice the river is polluted. We can clean the river, though. We can make those opportunities. If we wanted to, we would.