When the virtual hitches a ride on the ideal

Big Tech jumps the turnstile

1.

It‘s come to my attention that in the fashion world, luxury brands sell two tiers of products. The first is for the “rabble” — the high-powered lawyers, not the billionaires. Products in this tier are emblazoned with logos as an advertising tactic.

The second is the good stuff. If you have to ask how much it is, you can’t afford it. It doesn’t have logos. It’s an unmarked shirt made of baby pandas that lets one celebrity whisper to another, “Oh this? Prada. Yeah, the baby panda one.” The virtual gets marketed to the “masses” as the ideal. The profit this generates lets a few people snap up what little is left of the real.

2.

I’m not familiar with the dense theory of terms like “the Virtual” and “the Real.” I’ve read the Wikipedia pages for Baudrillard and Deleuze and that’s about it. When I say things like “ideal” and “virtual” and “real,” I very much mean them with lowercase letters.

When you press us on it, us laypeople do know that the virtual is its own special thing. We have eyes. Few mistake the metaverse, cryptocurrency, or anything else that’s overtly virtual as being real or ideal, especially if it just faceplanted in public fashion.

Those are recent, glaring exceptions to a general rule: when not pressed on it, most people don’t actually care to distinguish between the virtual and the ideal. Both words mean “non-physical.” Examples of each will fall into that bucket together, if we’re not careful. That’s how they get us.

3.

Rather, that’s how they make us get ourselves. A recent essay by Rayne Fisher-Quann about what she terms “micro-individuality” shows this clearly. We conflate virtual versions of individuality with real and ideal ones all the time. In optimizing ourselves for social media and employers, we make ourselves “stand out” in ways that neither accept our real selves nor move toward our ideal ones.

a song needs to put a few new notes atop a standard chord progression in order to be a viable product; a bag of chips might need to justify its existence through a different coloured package or new caloric density. the maximally rewarded object within a capitalist system is a product distinct enough to be sold, but not so distinct that it veers away from consumer demand. on social media platforms, people are the products — and so we are encouraged to become this kind of object, too.

Actual individuality is tough for capitalism to stomach; companies and online environments prefer a watered-down form. We are financially incentivized to present our most consumable, commodifiable selves, even if “be your best self” is found in the company brand guidelines. To continue the “people as food” metaphor: “best” or “most delicious” does not align perfectly, as the operations of the actual food industry show, with “best-selling,” “most addicting,” or “most palatable to the most consumers.”

4.

Jenny Odell, in her latest book Saving Time, discusses something similar: the way many of us view time, though less self-inflicted, also reflects a “virtualizing impulse” of capitalism. Factory owners and Amazon fulfillment center algorithms subdivide time down to the hour, minute, and second. Wiping your forehead while delivering a package? Get dinged. Time is money as long as you can track it in Excel. It helps for accounting purposes to treat time as a pile of uniform and discrete blocks, like shipping containers stacked up at a port.

Odell hasn’t come out and said it yet (maybe she will, still reading) but it struck me that this factory boss way of looking at time isn’t really a different way of looking at time at all. It’s a cheap virtual layer on top of the way real time is. A mass-manufactured fiction. Underneath that fiction, time exists as it always has for humans: a fluid thing, speeding up or slowing down depending on your situation, e.g. your adrenaline. Alongside the more mundane chronos, we sometimes get tastes of time’s “ideal,” a form of it bursting with urgency and potential that the Greeks called kairos.

Looking at time as eternally-divisible chunks of profit is a choice, an approach, a bias, a way for people to impose one type of time on others so they get to enjoy a different type: real time, vacation time, dream time. For most people, uniform time, virtualized time, “time as money,” is not a ticket to possibility and prosperity; it’s just stale, stressful, depressing, nauseating.

5.

The metaverse is but a shaky little building sitting on the surface of immense tectonic plates — larger, older, less visible ways in which capitalism has been “virtualizing” things around us since long before computers were around.

A recent blog post on Hacker News treated the “gridification” of the world as a beautiful thing, basically writing a love letter to it. The visuals on the page are great and the author does get at a real feeling, namely the exhilaration of the infinite possibilities of virtual worlds, but it gave me the heebie jeebies. It has the energy of a computer from Tron sucking someone into cyberspace.

There’s an element of cultlike coercion and faux-inevitability about so many virtual worlds, so many capitalistic notions of time, space, money, and much else. It’s not that the hippies are right and time and money aren’t even real, man. It’s not that these concepts are part of “The Matrix” or a “Deep State conspiracy,” foisted on us by a small cabal. Humans cultivated them and made them real. It’s just that there are other real, factual, historical, systemic things that have also caused them to fester; their manifestations in our lives now ooze phoniness.

6.

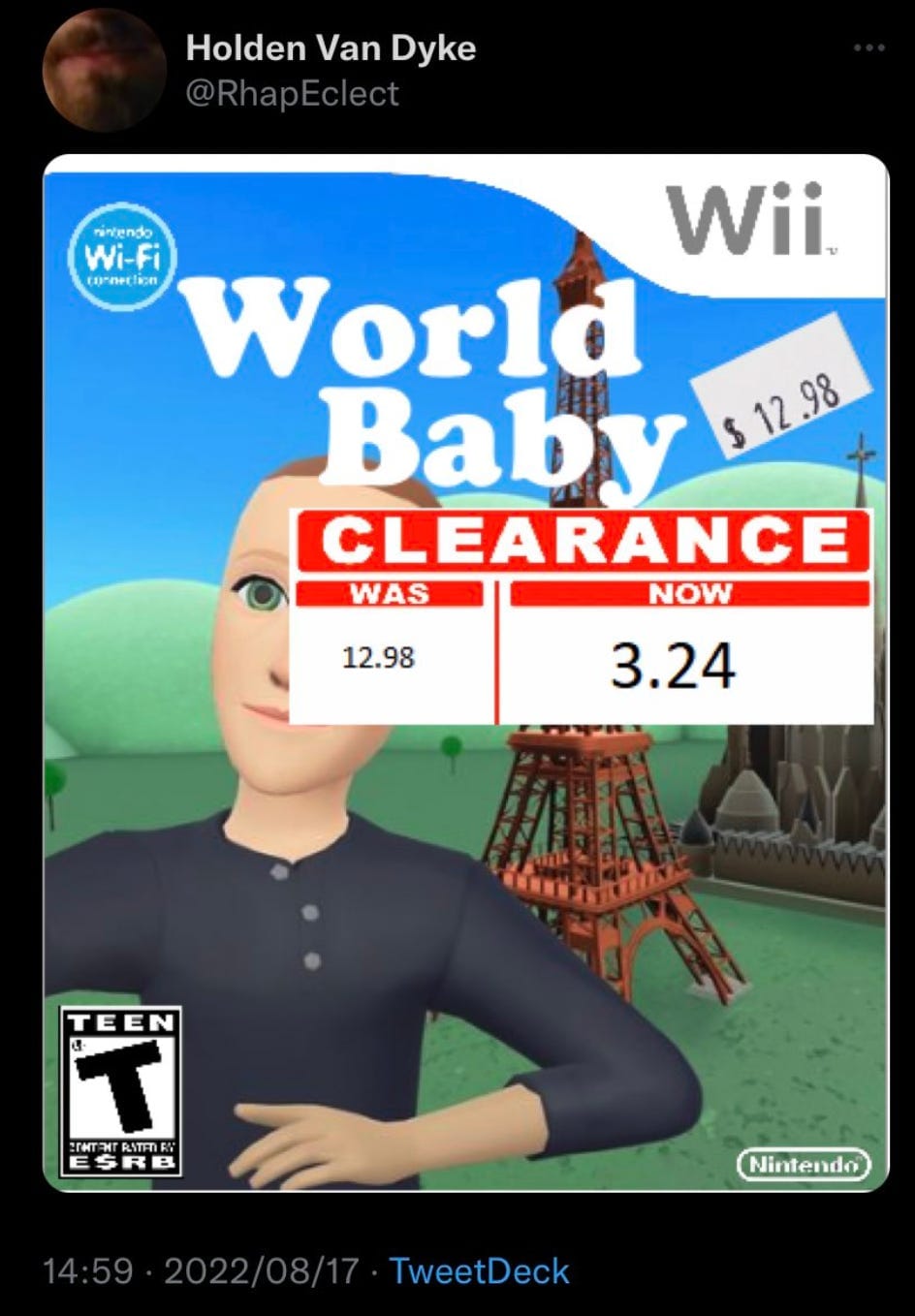

From the little I do know about Hegel, I know he would have giggled and rubbed his pasty hands together to see the public flaying of Meta’s metaverse. The lowercase-m metaverse was already an ideal in the public’s mind, a mostly grimy yet thematically rich set of cyberpunk worlds depicted since the 1980s. Nothing could have been further from this than the material conditions in which Meta’s metaverse sprang up: Patagonia-wearing Silicon Valley types, white tech bros, operating in a heyday of grift. It reeked of the sterile, the transactional, and the mundane. The ideal of “the metaverse” was one of the coolest things humanity had created and the rollout of “The Metaverse” was one of the cringiest.

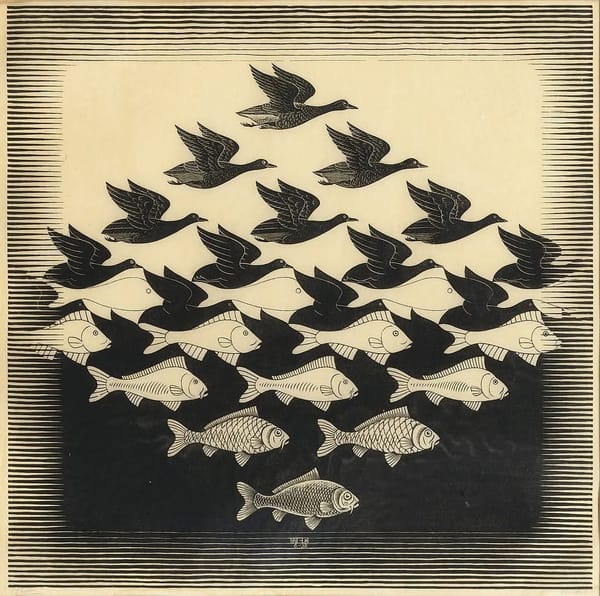

We’re more immune to this sort of thing — conflating the ideal and the virtual — the more we remember that things in both categories still arise from real people, places, times. They are rooted in us and in material conditions with unique identifiers and histories. A virtual thing can reflect something ideal. It can cover it up. It can tug it somewhere else in the public mind. It can never consume or replace something ideal entirely. Those vast tectonic plates, the virtualizing impulses of capitalism, moving beneath us, pushing virtual trash up to the surface, can still only do so much. They can yank our ideals this way and that, limiting our imaginations, mooching and leeching off of them, co-opting cool and authentic things and selling cheap copies of them back to us, adding impurities and “monetizability” to notions of time and money and friendship and love and work and play and everything else. But our ideals can always grow sharper and better-defined in response.

The wardens of our virtual worlds want no one to remember this. They want us to see all virtual and ideal things as forever interchangeable, detached from history, floating around in pure, abstract, Platonic vacuums. Thinking anything else is, to them, a “woke mind virus,” getting in the way of people treating their virtual endeavors as squeaky clean and unobtrusive. They want us to think their technological efforts are always perfect mirrors of collective ideals like possibility and prosperity, never dark mirrors of their own ideals of profit and power. The final piece for them is our going along with it, our wholesale ignoring of material conditions as we inhabit virtual spaces. This helps them herd us like livestock toward twisted virtual mirages of our ideals instead; with our money, they can then buy up the last baby panda shirts before they go extinct.

7.

It sort of adds insult to injury that the very model, the template, for the richness and never-ending differentiation promised to us in virtual spaces is just…the real world. The World Baby cover shows real European landmarks. When we bite this bait, giving in to the fantasies and paradises capitalism sells us to stay alive, we let our material addictions and poisoning of nature continue.

Like, okay. The real world isn’t always better. Ever gotten a rock in your shoe? Sucks. But the million dollar question is not as simple “real or virtual?” The virtual trash itself isn’t what’s dangerous. World Baby seems (mostly) harmless. It’s the way it distracts us, in so many forms, old and new. It’s the things it distracts us from, like our ideals and each other. We sacrifice these to engage with the many virtual layers placed over the real world, some by capitalists and some by us doing their bidding. This rampant virtualization is like a species of engineered corn that temporarily increases our lot in life, our food security, but it boxes out all other species of corn, ultimately making us more vulnerable to famine. Or a type of fool’s gold that gets marketed as real gold, but in fact has to consume real gold in order to grow.

The million dollar question is rather “how much more damage to the real is worth a marginal improvement to the virtual?” Given our recent track record I’m growing inclined to say “none.” Too many rugs have been pulled. Too much virtual trash has been peddled as ideal treasure. No more metaverses until we figure out what’s going on! I understand that I may sound like a wet blanket, a Luddite, a bitter Marxist, but if you think [new platform / algorithm / wearable device] will be different and make us all free, I say to you: oh will it?