Waterslide brain

Dark flow and the siren song of effortlessness

.

He want it easy, he want it relaxed

Said “I can do a lot of things, but I can't do that”

Two steps forward and three steps back, it won’t be easy

— The Strokes, The End Has No End, 2003

.

When I resolve to play with dice no longer, my friends depart from me and leave me lonely.

— Gambler’s Lament, Rig Veda, c. 1500 BCE

. .

I’ve said things to the effect of “technology isn’t good or bad, it’s how we use it” before. I’ve wised up. Humans are messy and we inject that mess into everything we build. The Internet is no exception.

That being said, there are vines that can either make your stomach hurt or make you trip for 12 hours depending on how you prepare them. There are fish whose venom is fatal but which, prepared right, are delicious. There’s the way the Internet inherently works and the way humans are making it work, perhaps intertwined but not exactly the same.

. . .

Zebras don’t get ulcers. Our brains, while different from those of zebras, also evolved to respond to things like tigers. Most of us no longer face them. Our bodies and brain stems don’t know that. They continue to respond to modern events with biological machinery made for tigers. What creeps up on us now? Ulcers. Anxiety disorders.

Our bodies treat the Internet like a swarm of captivating flies, following us around, at times useful and at times irritating. They let us communicate from across the savannah; they tell us helpful things about plants. We’d be crazy to give them up. We do notice that the flies are starting to interrupt us more and fight amongst themselves more for our attention. The people in our clan that we trade berries with to get them? They’re changing how they work in this way. They like spending all day eating berries under a palm tree. Who wouldn’t?

Sometimes we’ll be trying to concentrate on an antelope we’re hunting and find that even though we left our fly swarm back at camp, it’s harder than it normally is to keep our attention on the antelope. Sometimes it’s the opposite: we bag a few, but we stay out too late hunting more, and the meat from the first few begins to spoil.

. . . . .

It was an alarmist prophecy in 2003, the subject of Vice documentaries by 2013, and common knowledge now. Social media works like a casino. The thing about casinos: you can’t beat the house.

In The Cargo Cult of the Ennui Engine, Max Schlienger points out that the coins we invest are bits of emotional energy. We don’t get enough back, which is to say we get enough dopamine spritzes and fun updates from our friends to keep us there, but we don’t break even. We don’t get enough back to feel socially fulfilled in the ways we evolved to. This plus the Internet’s incentive to spread content that’s easiest to consume creates an interesting vampiric dynamic.

Since we’ve already demanded that we be served only low-effort content…we’re doomed to lose every time. We point to tiny blips above a baseline of boredom as evidence that we’re still enjoying ourselves, and we deny that our banks [of emotional energy] are being depleted.

…

Perhaps we pretend to feel a connection to a streamer, typing our in-the-moment thoughts to them instead of setting an hour aside to converse with a friend. Maybe we hang out in a Discord server, choosing easy yet transient and shallow interactions over complex ones that could foster sensations of being heard and embraced.

I was born on a generational cusp that makes parasocial activity fundamentally weird to me, but I’ve seen and experienced the hollowing out of public spaces over the last few decades and its acceleration during COVID. I understand the draw. I’ve put a message or two in Hasan Piker’s chat. I used to tweet. When something I say in these spaces gets traction, when I see the little red dot with the number in it, the associated feeling obscures a very important fact: I don’t know these people, and pretty soon, no one, including myself, will remember or care what I just said.

. . . . . . . .

In his book The World Beyond Your Head, Matthew B. Crawford describes how some heavy slot machine gamblers stand at their machines for eight to twelve hours and develop blood clots, or get so absorbed that when someone collapses from a heart attack they don’t get out of the way when the ambulance people come rushing into the casino. One woman wore dark clothes so she could keep playing her machine and soil herself without anybody noticing.

Psychologist Mike Dixon and colleagues have been doing research into “dark flow”, which is another experience that can afflict certain gamblers, although I’m going to suggest how it might apply beyond the gambling context. According to Dixon, dark flow is a trance-like state of absorption that problem players can experience when playing slots. Some players call it the “slot machine zone.”

In the old days, you had to crank a pull handle to get a slot machine going, and then you had to wait for the symbols to line up to see if you might win. Nowadays, you just press a button, and you can win across multiple lines, which can be horizontal, vertical, diagonal, or zigzag. With all these combinations, it can be difficult for players to tell whether they’ve won or lost after the machine has finished spinning.

— From Dark Flow to Crossing Wendell’s Bridge, Pilgrims in the Machine

Flow: a state of effortless concentration where time melts away. Dark flow: flow but make it spooky. This passage’s last point is the crux. In normal flow your task lies in a sweet spot between easy and hard, so you exert effort, but the conditions of the task make it feel effortless. Operating right at the edge of your ability, you experience just enough success to be motivated by reward, just enough failure to be motivated by the thrill of the chase. This means a key element of real flow is feedback. Knowing how well you’re doing. Dark flow says screw feedback. Don’t worry about how you’re doing; keep pressing those buttons, baby. It disguises losses as wins; it makes wins feel disproportionately good. It obscures the outcomes so it can keep you awestruck with sheer stimulation, sheer variation, random number generators, graphics artists, generative AI.

Press a button, new things happen. You skip past effort and into the feeling of effortlessness. You’re not directing your effort well; you’re not directing any at all. Real flow involves decisions and choices; dark flow involves the illusion of these. Real flow involves productive resistance, “desirable difficulty,” overcoming challenges; dark flow has you falling down an infinite path of descent, like a machine learning algorithm.

Many apps take the flow we experience while doing normal things, like interacting with friends, and add dark flow. It may not feel that different to be scrolling your Instagram feed versus DMing your friend a funny meme you found there, but there’s a difference. (Next time an elderly relative questions you for sending a meme to a friend sitting ten feet away from you, tell them you’re saving humanity, and direct them to this paragraph.)

If this still sounds too fuzzy and you want to know exactly how much effort separates dark flow from normal flow, too bad. The Internet enables both. It blends them. It’s extremely profitable for tech companies that we often can’t tell, in a given moment, how much of the flow you’re experiencing comes from each. Are you setting healthy boundaries so you can do your productive hobby? Are you just being indulgent, avoidant, lizard-brained? Boy, it sure is taking a lot of emotional energy to figure it out, huh?

The recipe: take things that are worthwhile, naturally desirable, and good at harnessing normal flow; gradually inject dark flow into them. Repeat. Make billions. We’ve all set up our own IV drip and now the nurses are raising the concentration of fentanyl in our bloodstreams.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

In a move I can only applaud, Nick Carr gave his book The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains an incredibly clickbaity title. For one thing, the book spends its whole first half on information technologies besides the Internet. Maps, clocks, books. When it does get to the Internet, it’s transparent and levelheaded, almost annoyingly so, about its benefits. Our visual ability to scan and process information, like on information-laden screens and in video games, has improved. Lastly, he admits that even if the Internet changes us in ways that aren’t strictly for the better, the tradeoff is often worth it.

Take writing. Just to hear about some event, a battle maybe, we used to need to listen to some dude drone away in the town square with a poem he wrote so he could remember it more easily. One could argue that this is better and more “natural” than writing; there are fascinating stories in the book about how long it took us to start doing things like “reading silently” or “putting spaces between words.” But like, I’ll take a newspaper.

The Internet, in a very real sense, is just a continuation of this. The legwork of storing and transmitting information has decreased yet again and dramatically. Globe-spanning distances: gone. A single meme sent to a friend can bundle a quantity of inside jokes and cultural references that would take days to explain to a Victorian street urchin. At no point in history have we been able to communicate so quickly, with such complex patterns, made of so many types of media, all at once. (Next time an elderly relative questions you for sending a meme to a friend sitting ten feet away from you, tell them you’re embodying human ingenuity, and direct them to this paragraph.)

Where Carr goes wrong is epitomized by how much time he spends talking about hyperlinks. These absolutely show the distracting nature of the Internet; links raise countless micro-decisions of “do I go here or not,” draining mental resources silently and in the background, decimating our ability to concentrate. No matter the source of the switching, switching tasks and focusing on a single task are different skills. As we practice one and abandon the other, our brains change accordingly, creating downstream effects for our ability to think deeply about things and store them in long-term memory.

All these things still apply, but for reasons that weren’t as obvious in 2010 when the book came out. Interruption doesn’t look quite like it used to; hyperlinks are far from center stage. On most apps, even though you can follow links out to other places and dive down long comment threads, the norm is not that. It’s a feed. It’s scrolling.

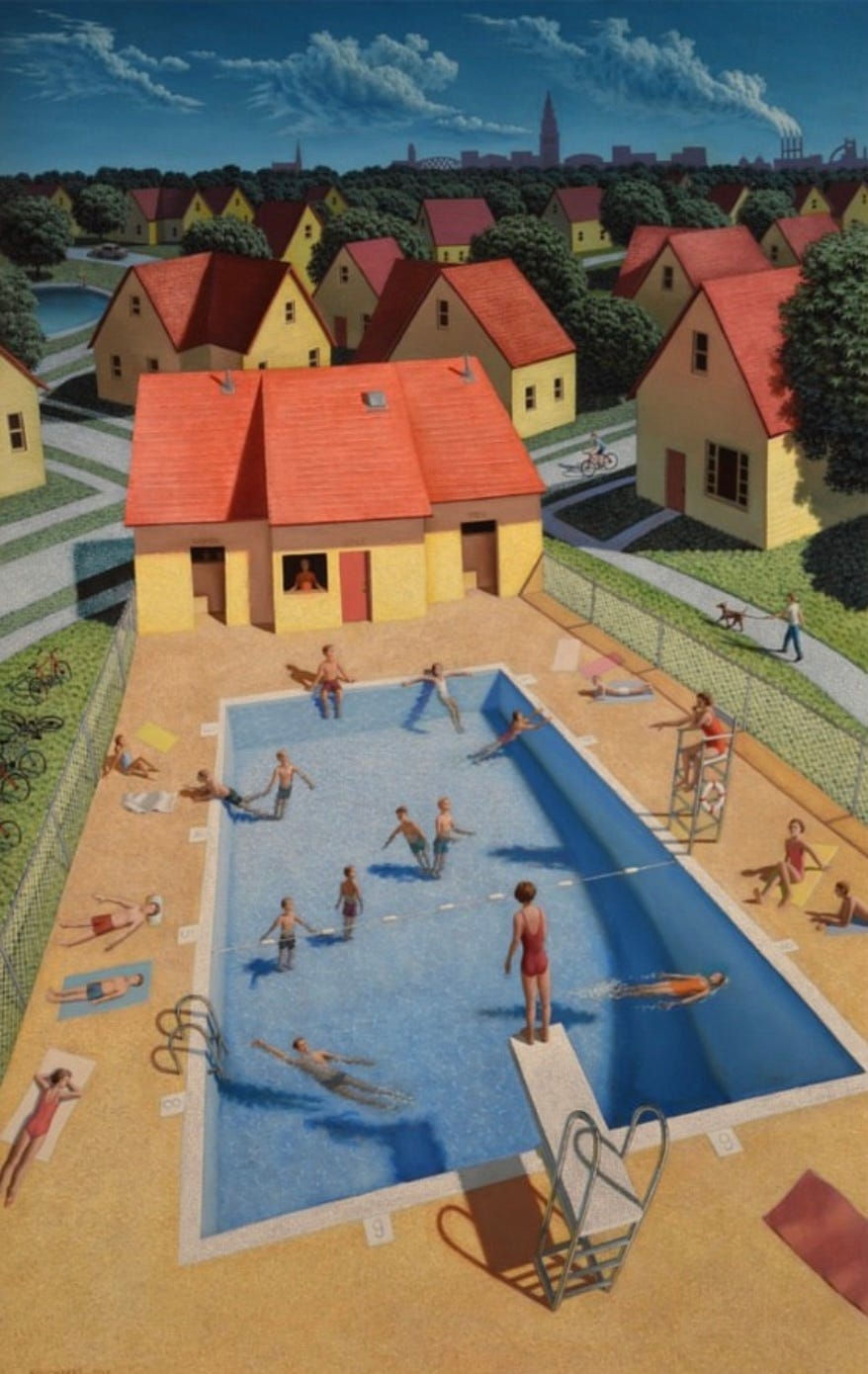

It’s constant interruption and “seams,” sometimes every few seconds, but in a way specifically designed to be as seamless as possible. Where once it was all hyperlinks on a webpage, now it’s a list of tweets, or videos, or whatever else. (Sometimes I scroll houses on Redfin.) The Internet is no longer so much like a maze, where every few feet you can freely choose to turn in a new direction. It’s a waterslide, sometimes branching off into a few different chutes, but built to make us not fret over which one to pick. We let gravity take us where it will.

The content can still be effortful; Substack, for example, is a gold mine of long-form content. But they recently introduced Notes. The ethos of social media spreads. It’s not about what’s easy, full stop, but what’s easy to you. The hydraulic pump of the profit motive forces the walls of the Internet’s walled gardens inward. Our choices become more illusory in the name of things being “frictionless.”

We largely don’t mind. We want something easy in a world where many things are hard. We tend to think of the Internet and the safe, fuzzy feeling of dark flow as one mental environment, and one that we fully choose to engage in, and the rest of life as another. We go to a casino; we can pull the slot machine or not; then we leave. We go to an app; we can like something that appears on our feed or not; then we leave? If The Shallows does one thing right, it’s explaining why the brain, an incredibly plastic organ that changes as its tools change, can’t “leave” the Internet in the same way.

Carr finally touches this aspect of the Internet and AI more generally at the very end. AI wasn’t so far along in 2010, but it had started to customize our feeds. Since then it’s gotten its fingers into many more pies: not just the presentation of content but detecting patterns in it, summarizing it, generating it.

He notes how the AI villain in 2001: A Space Odyssey, HAL 9000, ultimately sounds the most “human” of any character. The humans have outsourced so many capabilities to it that they themselves have become fairly machinelike.

While the issue of becoming machinelike is applicable, it’s not quite the central problem. The problem is the removal of effort, the removal of choice. One can still be very human, yet have choice removed from you by human authority, a brain implant gone awry, or the casino-fication of every app. One can theoretically be a machine that can make choices. What’s going on is automation through sedation. The problem is not just becoming robots, but specifically robots who have been programmed by the dark flow of online environments to accept the dark flow of others’ choices.

Forget for a second about whether AI will “replace us.” We could hardly be doing a better job of setting ourselves up to be replaced by it. We’re getting good at the things it can most easily do for us: fleeting visual things. We’re getting worse at precisely the things AI can’t and won’t replace anytime soon: deep, creative, highly focused processing of abstract patterns and concepts. This includes the knowledge of how to break those patterns in innovative ways.

If and when electronic telepathy comes along, the issue will not be that it speeds up the transmission of communication between people. That will be the awesome part. The issue will be: what patterns will we even share? What if all we have left are snapshots, flashbulbs, sense impressions? What if that technology is the spaceship from WALL-E, and people’s minds become the atrophied passengers, devoid of the ability to experience and enjoy the galaxy because they’ve turned over their ability to ponder, to share complex patterns, to the machine? What if the workings of the machine become so much like witchcraft to people that it becomes no longer common knowledge, but a shadow on the periphery of their consciousness, that a few tech execs and their programs are out there, experiencing real life, handling everyone else’s patterns and choices for them, and poorly?

. . . . . . . .

In the yard, just past the deck railing, bad plants are entangled with good.

The good one is a yew, a bush with low branches over a broad area and needles like a pine tree. The bad ones are white snakeroot, whose leaves are poisonous to the touch, and eastern nightshade, whose berries are poisonous to eat, which our dogs don’t know.

I’m on my last snakeroot. On one side of it is a landscaping stone. Surrounding the rest of it is a dense intersection of yew branches. I’m able to move the branches long enough to get in there.

I weave the shovel around the good branches and kick it from awkward angles to dig up the roots. Sometimes the roots can be pulled, but for the nightshade I then have to clip branches strategically and pull them away gently to not scatter the berries everywhere.

There are no clean edges here. Instead of “degrading gracefully,” as software does, things that go wrong do so in weird ways. Challenges are not catered to your abilities. Sometimes when digging up bigger pests like buckthorn you just have to cut your losses and pour StumpStop on it.

The thing is, once you call it a day, you feel like you deserve a treat. And when it occurs to you that there’s always more out there — maybe you discovered a whole new patch of snakeroot elsewhere in the yard — it’s different. The effort you’ve just put in has made you more, not less, able to tackle that later.

Interestingly, even as the weather cools and the mosquitoes bite, I don’t want to quit. A little more so than usual. A similar thing happened a few months ago, trimming mulberry trees for too long and getting a little sunburnt. Is this me naturally being stubborn, hard-headed, tunnel-visioned? Am I just enjoying the task more than usual? I want to say that.

It also feels, in a way, like scrolling and not wanting to stop.

. . . . .

A father goes to his son’s room just before dinner and informs him that the woman is back. So begins Ignore It, a short horror film from 2021. The woman herself turns out to be a stock villain, a grayish-blue demon lady whose face you never really see. It’s what isn’t shown that unsettles you, as with all good horror.

At the table, family members remind each other not to acknowledge her. It wouldn’t be a horror film if all went well and they succeeded. The mother confronts the beast in the kitchen and meets a grisly fate. We see from another character’s actions that stealing a glance at her in a reflective surface is also unchill. Through everything, the father tries to keep the ignorance going, and then tries to protect the family when all hell breaks loose. Concretely speaking, he takes all the actions that maximize the probability of keeping his family alive.

The allegory is strong with this one. Certain problems of the modern era have been “out there” for a while, gathering steam, metastasizing into other things, having side effects that are hard to trace back to the original problem, and then: they “come to dinner.” An elderly relative says something mildly brainwashed during an otherwise pleasant dinner; you could try to change her mind, derailing the conversation, likely entrenching her in her opinion, or you could not.

Sometimes attacking these problems in the most direct, intuitive way, the head-on way our caveman bodies tell us to, can be ineffective, wasteful, and even harmful until we deal with certain bigger forces. Sometimes attempting to solve huge global problems through individual or small-group actions can feel warm and fuzzy, but can be the rash and cowardly act, while keeping your cool, “ignoring it,” can be the brave and level-headed one. The true horror of Ignore It comes not from the demon lady, but from the characters being thrust into a situation where she can visit anytime she likes, and where the instincts they evolved with are completely maladaptive to stop her.

In real life, of course, we have some amount of collective control over how much she visits. But there are people who, when the lady isn’t around, are not like that dad would be, looking for ways to banish her or ways to better protect the family from her. They’re looking for ways to make us lean into our instincts. Invite her back. Be less safe from her. Forget about how she works. Be unable to choose to protect yourself from her; people getting killed by the demon lady drives views and clicks.

. . .

A morning trip to grab breakfast at Colectivo. No mere storebought bagel and cold brew concentrate. A moment of simplicity and convenience. A moment of Americana, lifted from the sixties, except even better. Better flavors. An app you can order from in advance.

Of course, there are differences. My stomach is uneasy when I get into the car; am I hungrier than I thought, or did some white snakeroot get past my long sleeves? It killed Abraham Lincoln’s mom, you know. I discard this idea; you’d have to drink milk from a cow that’s eaten handfuls of it to see effects the next morning. I briefly wonder if it’s moving north as the climate changes. When I get there I park in a spot whose no parking sign I, ahem, didn’t see (only for like 30 seconds, in a place with no fire hydrants, no red lines, no handicap-accessible curbs, nothing). It goes fine as always. I don’t get towed. I briefly wonder if the person living at the house I parked in front of is one of those people on Nextdoor who’ll post your license plate everywhere.

These two things I briefly wondered weren’t pertinent to my journey, but there they were. They didn’t so much exist here (gestures immediately around me) as in two other places: “out there” (gestures broadly) and in here (points to head). One layer: broad and diffuse forces, outside individual control. Another layer: internal psychic weather, anxieties, desires, your own psychological shit mixed with the world’s. Wispy, near-invisible threads connect the inner and outer layers throughout the middle layer, traveling through it like spiderwebs. Profit motive. Cultural chauvinism. They weave around, not confrontational, creeping at the margins, polishing up this middle layer, an increasingly pristine and inviting veneer. A world of air conditioning and video games. A world that makes life so bearable that we can, with increasing ease, ignore the other layers and lose ourselves in it.

. .

“Go with the flow.” Whose, though? If you go with a flow created by someone who’s gradually taking choice away from you, you eventually won’t be going with the flow at all. This is because, if there’s no going against the flow, then there’s no sense in which you’re “going with” it, either. You’re not doing or choosing anything. Others are, for you. I mean “for you” only in the mechanical sense. To be clear, they’re doing this for themselves.

Like, I don’t wanna be Johnny Rose from Schitt’s Creek, throwing a tantrum because no one is putting effort into the Christmas party he proposed on Christmas Eve. I understand that we’ve all been through some things, and dark flow is easier to choose, and hard to separate, and not even inherently bad every time you indulge it. I’ll just leave you with what Terence McKenna once said: take it easy, but take it.

.

I descend a steep hill by a waterfall. I touch the water without realizing it and it shunts me downhill. I fall into a cranny that’s surrounded by steep rocks. I can’t get my character out. I load from my blessedly recent saved game. On the loading screen, a thought occurs. What if, way off in the mind-uploady future of humanity, someone’s consciousness were to get trapped, Aron Ralston-style, by a bug like this? Imagine it: some mundane technical error locks someone in digital purgatory. An inept corporate bureaucracy forgets about them. They’re left to stare forever at nothing, or at a cryptic dialog box, unable to escape by any means available to them. These virtual delights have virtual ends.

.

We’re biking. The smaller of our two dogs is strapped to my fiancée’s torso. He’s smelling more smells per minute than he has in his entire life. I joke that he’s scrolling through his feed. He isn’t, of course; I know this because at our destination he’s as happy and relaxed as he’s ever been.