Make Virginia Flat Again

The true story of Bacon’s Rebellion

1.

Virginia was a sea. Trilobytes were everywhere. Then mountains. Then a sea again. Then swamp. Then sea again. This went on for a while.

The sea retreated for good (well, don’t speak too soon) late in the reign of the dinosaurs, who frequented the area. There’s a spot a couple hours outside DC with so many of their footprints that paleontologists call it “the ballroom.” Many millions of years later, woolly mammoths moved in. In the early 1700s enslaved Africans would point out (to incorrect white paleontologists who thought they came from mastodons) the similarity of their fossilized teeth to those of African elephants, which are closer to mammoths.

One of the last new arrivals in this area: pigs. “The story of Bacon’s Rebellion does, ironically, start with pigs,” begins one website. Cute, but to get to Virginia, they needed one extra factor: white people in boats. As people from Ghana to Hawai’i to Japan have learned, look out for white people in boats.

The British established Jamestown in the early 1600s, about halfway between present-day Norfolk and Richmond, after a mysterious false start.1 The natives were much less confused by our pigs than our notions of property rights, which they still struggled to grasp by the 1660s, for the same reason it’s hard to understand “2+2=5.”

Clear-cutting large swaths of forest? Totally cool. We can destroy a little native habitat, as a treat. But a couple pigs go missing? Hoo boy. Clutch your pearls. Grab your rifles.

2.

60 years was absolutely enough time for deep divisions to form between the Virginians who liked to clutch their pearls and those who liked to grab their rifles.

After the natives taught us how to cultivate tobacco, it caught on in Europe in a big way; as they would say in a VH1 documentary, the band got too hot. Tensions flared. Virginia’s rich upper crust, bureaucrats and tobacco plantation owners, became ever more possessed of certain notions about themselves, armored with certain narratives.

It had grown common for them to strike deals with poor Englishmen (“you work my fields for a while, I take you across the Atlantic”), but clearly it was their own nobility and vision, their own divine aura and enlightened grace, that made every piece of this colony possible. Through them and them alone, they felt, were these dusty white farmers blessed with the privilege of tilling their fields in the first place.

In retrospect, it was risky for them to keep up this “and don’t you forget it!” attitude, even after so many of these indentured servants had worked their way to freedom. But that they did. They kept on hoarding tobacco taxes, smugly sipping their newfangled “coffee,” and reserving land and jobs for their friends back in London. If disputes between farmers and natives arose, they told farmers to build some forts and get back to farming ASAP please.

Officials were prospering. Natives, using centuries-old land management techniques that were actually, like, good, were prospering. The colonists grew bitter. They didn’t like what they saw. Though technically free, the dumb hierarchical system they had bought into was suddenly leaving them at the bottom and suffering.

One year they watched their tobacco crops fail. They watched the governor watch it fail, and shrug, and continue taxing the bejesus out of it. The powder keg of their rage was ready for the spark of someone saying: “it’s everyone’s fault but yours.”

3.

They developed itchy trigger fingers. They began to retaliate disproportionately against natives who resisted white encroachment, and when they did, they began to exercise little discernment in figuring out if the natives in their sights were part of the tribe who stole from them or not. It was as if they needed to distinguish themselves from the British officials, content to try and hold the natives at arms’ length.

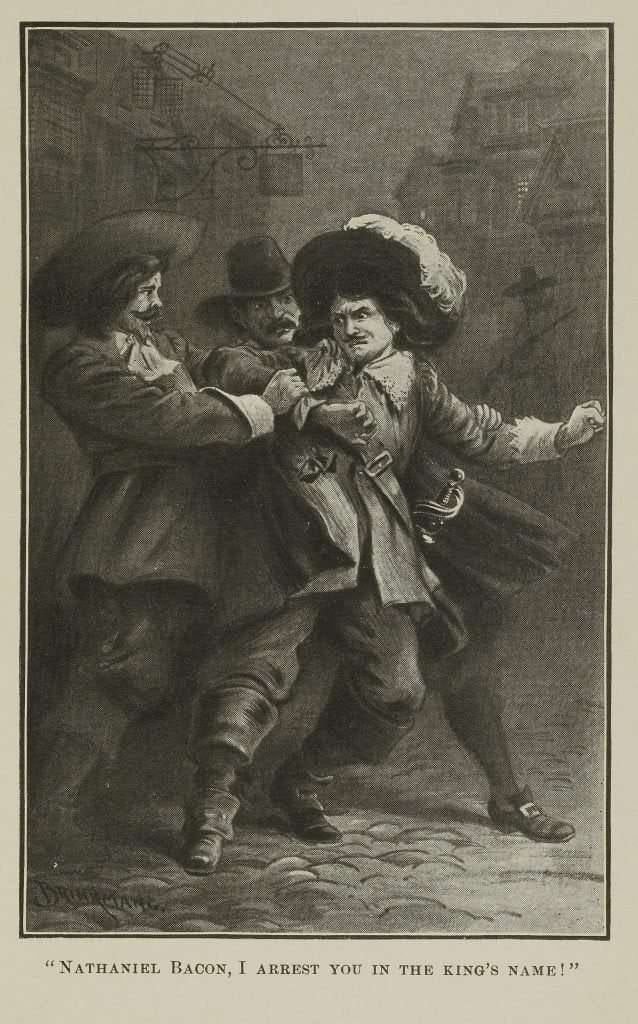

Nathaniel Bacon was not a frontiersman or former indentured servant at all. He was a rich kid. His father was a friend of William Berkeley (Virginia’s governor at the time) and he himself was on Berkeley’s council.

In the itchy trigger fingers of these frontiersmen, he saw opportunity. He whipped up their rage at natives and British officials. None of them had ever driven a plow, the only tool one should live by, and if crops fail — say it with me — “it’s everyone’s fault but mine.” He painted the natives as savages and the officials as parasites, undeserving of the authority with which they bossed colonists around and bled them dry. He was half right.

His coalition of the disenfranchised melted their bitterness into a big pot, despite some flavors being far more righteous than others. He enlisted freed slaves; in Bacon’s silver-tongued leadership, they saw a chance to win influence, respect, and dignity that the Crown had denied them.

He began convincing this mob that drastic, bloodthirsty measures were needed to show both the natives and the colonial government that they weren’t to be trifled with. He took them on increasingly ambitious killing sprees in indigenous territory. He would even get help from native tribes who had beef with Berkeley’s regime and/or whichever tribe he claimed to be targeting that day, and then violently double-cross them.

These actions brought a spike in native hostility toward the British, annoying Governor Berkeley, who stonewalled Bacon’s requests for more resources to fight natives. Bacon’s followers didn’t take this well, perceiving it as paternalistic inaction: “you colonists sit in time out and think about what you’ve done.”

During a particularly well-stocked and well-manned rampage Bacon took his men on, Berkeley got fed up and declared Bacon a traitor. Hearing this, Bacon got fed up and set his sights on Jamestown.

4.

The ensuing skirmishes and encounters between Bacon’s men and Berkeley’s is best described as something out of Looney Tunes. Think Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd, or Wile E. Coyote and the Roadrunner. Much happened; the events are roughly bookended by two main ones.

One was a confrontation at the capitol, where Berkeley allegedly bared his chest and dared Bacon to kill him. Bacon didn’t. His mob instead got multiple laws passed at gunpoint, mostly about being allowed to kill more natives.

The other happened after a brief and tumultuous professional relationship in which Berkeley kicked Bacon out of the legislature twice. Bacon, at wit’s end, laid siege to Jamestown using human shields: women who were relatives of British officials. Berkeley took a “surprise vacation.” Bacon’s mob proceeded to burn Jamestown to the ground.

Bacon then fled British troops dispatched to stop him,2 caught dysentery, and allegedly died. His coffin was later dug up and found to be full of rocks.

The rebellion was squashed quickly after that. Berkeley made peace with militia leaders that came after Bacon, executed a handful of people in the lower ranks, and moved on. Mostly.

5.

The British elites, keen on preventing this from happening again, had unfinished business. Seeing plebs of many colors gang up like that really put the fear of God in them. But an idea occurred to them.

Engaging in the Transatlantic slave trade had always required moral gymnastics, but in practice, it had largely been carried out with a bullet and a shrug, not dressed up in much fancy justification. By changing this, they could hit two birds with one stone: bolster support for this trade, and keep workers divided and suspicious of each other.

The frightened imperialists embarked on a PR campaign. They began to make something new out of the concept of race, recasting it as something fundamental, practically scientific.3 As Michelle Alexander explains in The New Jim Crow, they highlighted and reimagined it as a deeply significant reason why white colonists should look down on black people, never feeling, no matter how bad things get for them, like they’re at the bottom of the capitalist totem pole. In short, Bacon’s Rebellion was not, as my high school AP history textbook said, a precursor to the American Revolution; it was a precursor to every instance of white backlash that would follow. Jim Crow after the Civil War. Mass incarceration after Civil Rights. 45 after 44.

Our present leaders, like Berkeley, alternate between big talk and useless hand-wringing. One of Berkeley’s lieutenant governors wrote that “a Governour of Virginia has to steer between Scylla and Charibdis, either an Indian or a Civil War.” Centrist leaders likewise play up our (extremely powerful) government’s paralysis with a smile and a shrug, equating the “populist excesses” of the people the mob wants to exterminate — immigrants, trans people, socialists, people who want a livable climate — with those of the mob itself. They will do anything except use the power our labor and taxes give them to stop the mob. Even if they eventually do, we have someone in power who practically built his career on mass incarceration in the 1990s and shilling for the banks; the best we’re likely to get is another “surprise vacation” when the mob lurches into town, followed by dramatic expansion of the surveillance state.

The question now is not whether another Bacon will arise, because one did. The question at hand is what we’ll save from them — which approaches to things like justice, labor, race, and land we’ll keep — and arguably more importantly, what we’ll leave behind.

Title photo: Arrest of Nathaniel Bacon, Encyclopedia Virginia

Roanoke Island in the late 1500s is a pretty crazy story too. ↩

Some interesting things would soon happen to these troops. ↩

This “science” would reach a fever pitch of bullshit in the 1800s; some still can’t seem to smell it. ↩